I had the pleasure to sit and talk with my former teacher and mentor Eva Amsler, Professor at Florida State University. Her teaching, performing, and philosophical view of life have encouraged others, including myself, to pursue a life in music that is true to oneself, joyful, and meaningful. I am excited to share our interview. – Amanda Hoke

AH: When did your musical training begin?

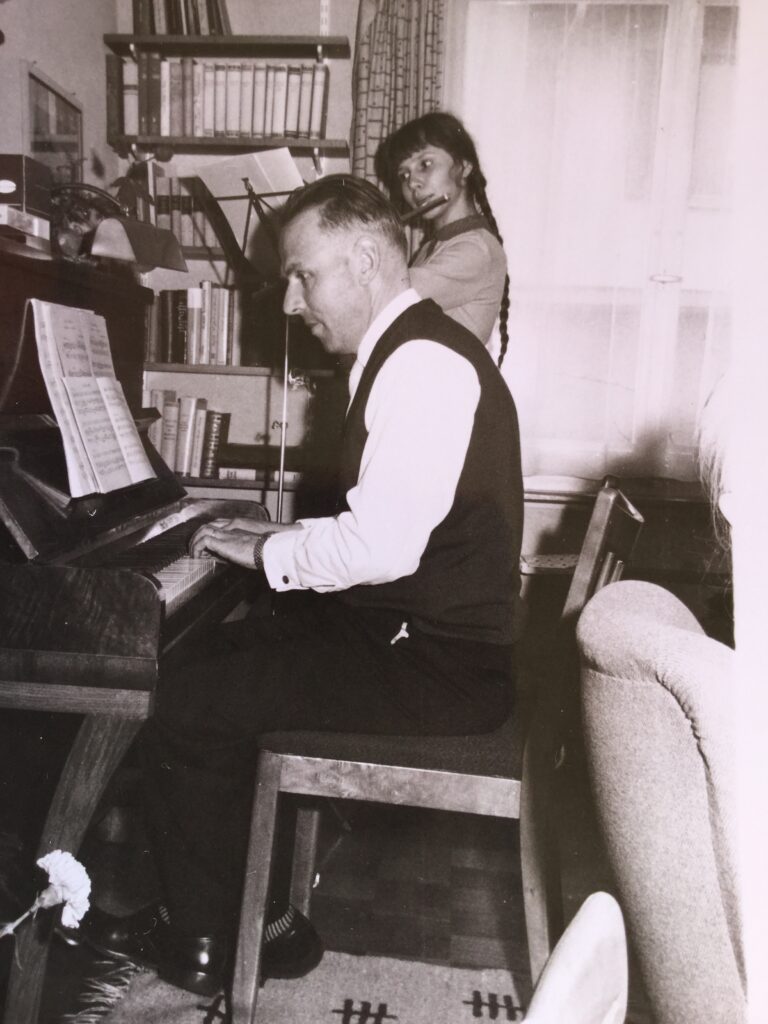

EA: My family was singing folksongs together as far back as I can remember. I often heard my father playing the piano upon going to bed and our night prayer when we were little was a song! So music was always a part of my life since earliest childhood. But I started on recorder when I was six years old. My teacher was a modern flute player, and the first time I heard or saw a flute was at one of her recitals. When I was 7, I played piano. I liked it, but I wasn’t as good as my older sister. And soon, when my younger sister started playing piano, she progressed faster on this instrument and became better than me!

Then, my older sister brought one of her friends home who happened to play the flute. She asked me to try it and I at once got a nice, full sound. Now we just had to convince my parents to let me play! I was 12 years old when I started. Until they were sure I would stick with the flute, they had me continue my piano lessons. But from the very beginning, I was very motivated and loved the flute way more than the piano. My parents could see what a good fit it was! I liked it best because of the sound. I grew up with a few records: the Magic Flute and Beethoven’s 5th. In the orchestra, the flute was the silver on the top, and I dreamed that I could be that silver lining on the top of the orchestra someday. In addition, we listened to Baroque music—a lot of Bach.

AH: I like that analogy of the silver lining on top of the orchestra.

EA: In my youth, I never said it out loud, but I wanted to become a flutist, a musician! You can read this in my journal all the time. I often ended my writing with a quote from Beethoven: “Music is…a higher revelation than all Wisdom and Philosophy.” The hesitation was the question: am I good enough? At the time it did not feel like it. My older sister very early on had the courage to let everybody know that she would be a singer. It took me until I was 18 to understand that music was what I was meant to do.

I think it is really nice to have a “calling.” As a child, I sometimes felt misunderstood, because it seemed that I could not express with language precisely what I wanted. But one day in a school concert, I felt this connection to the audience, that they were really listening to me…it was then that I knew that this is how I could reach people and be understood and share – through music. Music is my language. I felt that was what I had to do.

When I was 20, I graduated with my first degree: Elementary Education. I decided not to go into teaching, rather to pursue music by earning a Diploma in Flute Pedagogy. You cannot get that degree here in the United States, but you can in Europe.

During this time, I studied in Bern and Zurich with Günter Rumpel. My education emphasized not only the flute but also pedagogy, and this set the foundation for my teaching in the future. I also come from a family of teachers: both of my parents were teachers, my grandmother was a teacher, and so was my great grandfather. It was quite natural for me to follow this path.

AH: How did you choose a school for studying the flute?

EA: When I initially chose a school that I wanted to go to for flute, my first teacher Sunna Gerber (she was the first female to get a Bachelors degree at the Conservatory in Zurich!) wanted me to go to Zurich to study with her teacher, André Jaunet. He was a very famous French flutists, and Principal at the Tonhalle Orchestra Zuerich at the time. But I wanted to go and study with Günter Rumpel, who also has been a student of André Jaunet, as I really liked his playing.

So I went to Bern, I passed the entrance exam and enrolled. It was a wonderful time because I learned a great deal at the Conservatory in Bern. Günter Rumpel was all about the basics, how to practice, what is good repertoire, style and musical phrasing, and orchestral excerpts. I didn’t play my first excerpt until I was 22. That is really different than in the United States—most students begin studying excerpts much earlier here than we did at that time in Europe.

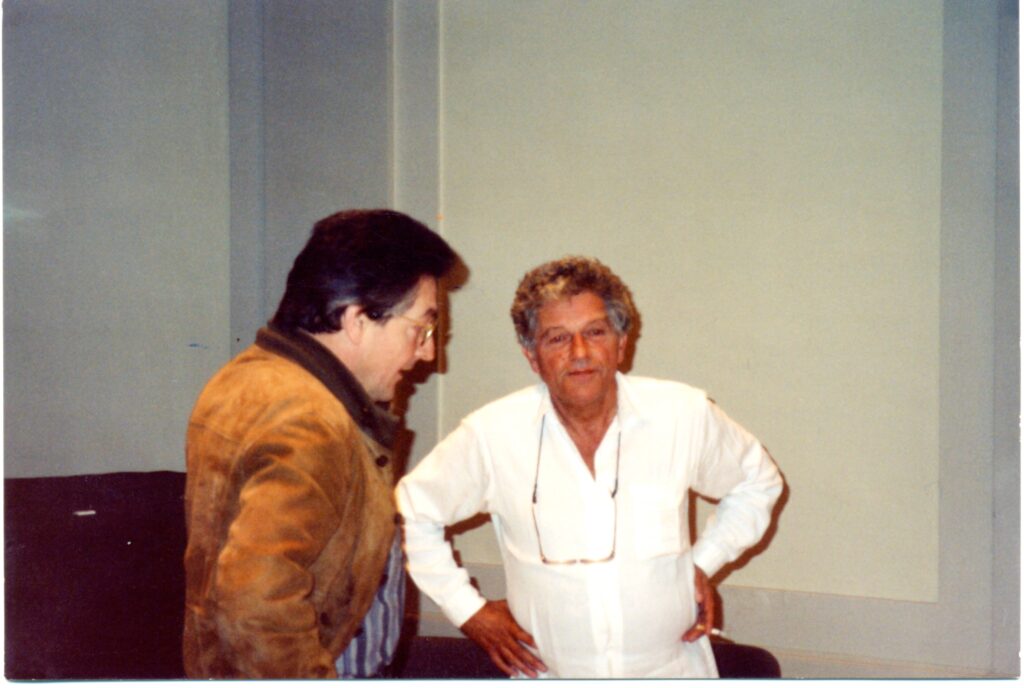

When I finished my studies in Bern, Günter Rumpel wanted me to go to study under Peter-Lukas Graf in Basel. Also he was a student of famous André Jaunet! But I had heard Aurèle Nicolet in concert performing CPE Bach concerti and decided to audition and hopefully study with him in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany. In 1978 I traveled to Germany to audition. Thank goodness I was not aware of what I was doing and how competitive it was: 50 flutists came to audition, a really high number back in 1978! I had no idea how hard it was to get in Nicolet’s studio and that he only took 1 or 2 new students per semester.

AH: Now I am curious about the audition itself. What was it like?

EA: The audition was scheduled and the repertoire was given. CPE Bach Solo Sonata in a minor, by memory, Carl Stamitz Concerto in G by memory and Berio Sequenza. Then sight reading. There was a piece of choice most likely French, I don’t remember exactly.

When I arrived for my audition, let’s say at 2 o’clock, there was a sign stating that the audition was moved to 3 o’clock. Without cell phones, there was no way to inform candidates beforehand and so this took me by surprise. I had prepared myself mentally for 2pm and now had to deal with this unexpected situation. The house where the audition took place was busy, no rooms to practice. It came to me that I could go to the church across the street and sit down and think through my memorized piece! Looking back, this was my first time using mental training – but without even knowing it.

At that time, there were no books about mental training. Nobody told me to go to a nearby church to warm up mentally—I just followed my intuition and went there to prepare and focus. I was not very good at memorizing music at the time. But in the church, I sat down and started going through each movement really really slow, hearing it, seeing it, knowing every single note. During the audition this helped me to play the CPE Bach a minor sonata the first time completely without mistakes! That was when I understood how important mental training is to performance, and from then on, I cultivated it as a skill.

As for the audition itself, I don’t know the exact number of current Nicolet students that were invited to come and listen to all auditions—the room definitely seemed crowded, my future peers all sitting on the floor. I played the CPE Bach, two movements of the Stamitz Concerto both from memory, the Berio Sequenza and a french piece for Nicolet and a committee of a couple of other teachers. He asked me to sight read one of Bach’s violone sonatas—since I was a good sight-reader, that was kind of fun! To my surprise in the end of the audition Nicolet asked me to come the next day in his studio at Urachstrasse to meet him there. I left the room and I thought, “Wait a minute, he cannot tell everybody to go to that house and meet him there the next day…”

After returning home, I waited and waited, but I didn’t get a letter of acceptance or denial. Then finally I worked up the courage to call and ask, and Nicolet said, “Yes, of course you are in. In the spring, you will study with me.” I couldn’t believe it.

I finished my studies with Günter Rumpel in April 1979, and I left right away to start studying with Nicolet. On April 1st, I had my first lesson. It was not an April Fool’s joke—it was actually real! He told me to play the Demersseman Sixième Solo de Concert for him, and afterward he told me, “Okay, I think we really need to work on technique. You are going to play French pieces in the next few weeks.” He required an étude and a full piece every week at lessons. You couldn’t play the same piece twice.

AH: That’s amazing. Did he only coach the music, or did he talk about any other aspects of playing, like scales or tone? You were at the level where you probably didn’t need that.

EA: Yes, I needed that, and in a certain way, I think, we never finish technical exercises… In lessons, we first had to play an etude. He had usually assigned an etude book for the whole studio. We’d come in, we’d play that week’s etude, and he often made us memorize them. We then performed the piece we prepared, often chosen by ourselves, and he worked with us on all aspects of music, but also technique and sound. Sometimes he would assign pieces like Mozart or Ibert, or he’d warn us to be able to play scales or intervals or chords in the key of the piece. He would just make you play the technical stuff through the piece. He had a big chart on the wall with all the intervals on it. Sometimes when you had difficulties to execute, for example the thirds in the Ibert concerto or in a Mozart concerto, he sent you to the chart and you had to play your thirds all 3 octaves chromatic or in the key of the piece in 2, really slow, in 3, in 4, in 6 and in 8!! Just like that, you had to have it ready. And if you have never done it before, you for sure start sweating.

AH: I can imagine that.

EA: He made us do exercises like Taffanel, Reichert or Moyse etc on the side. He also would make suggestions of other pieces, exercises or etudes that complement the main work you were studying. We had a second lesson with his assistant, covering only techniques, nothing else. The assistant flute teacher, Hiromi Horiuchi, was one of his former students. She never played for me in lessons—so no modeling, just talking. Then I had to try. I clearly remember a lesson where Hiromi talked about tongue placement. We in addition worked from another etude book in these lessons and we played all technical exercises by memory, of course.

AH: Was that prescribed, that she didn’t demonstrate? Was that meant to be that way?

EA: That was just her style. She did what she wanted to do. She was Nicolet’s student, but she taught her own way. I learned a lot with her. It really helped to have lessons with her, to be able to make fast progress.

AH: That’s interesting. And then?

EA: Nicolet asked me, “What do you want to do after these two years, after you get your artist diploma?” I said, “I want to go to the orchestra,” and he said, “Oh, you can try.” That answer felt a little sarcastic to me! Of course, he thought that it was really hard to get an orchestra job, and he was right! So I went to my first audition. I barely remembered to take my concerto with me. Nicolet was not the one to prepare us for the audition process mainly.

AH: You did that on your own?

EA: Yes, partly. I remember that once a semester, Nicolet would have an orchestra flute colleague come over from Stuttgart, Klaus Schochow, and he did flute excerpt classes for two days. Basically, we were sat in class for two days, learning mainly by listening to others play and taking notes. We also each had one personal session. That was it!

So I took my concerto to this first audition, just in case, and yes, the first round was Mozart. Of course I had studied it before, and so I was able to play it at the audition. I had low expectations because I had been sort of thrown into the whole thing, but I got to the final round!

AH: On the first audition? That’s crazy.

EA: The one excerpt that I had never studied before – I saw the list only a few days before the audition – was Smetana’s Bartered Bride. I had been practicing it only for 3 days…and I made one mistake…the other finalist got the job….

At the second audition, only a few weeks later, I advanced again to the very last round, and I was invited to the next audition. Again, I advanced to the final round but didn’t get the job. Then the third orchestra audition was for the St. Gallen Symphony. There’s where I won my first position and got the flute/piccolo job for one year. I won an orchestra job in my second year of artist diploma when I was 25. This was a big change and success. I didn’t necessarily decide to do all of that, it just happened.

AH: Yes, it just came to you.

EA: Of course, I have to say that during that year in Freiburg, I practiced 6 to 7 hours a day. I barely did anything else.

AH: You need that.

EA: One year after those auditions, in 1980, I finished my studies and graduated from Musikhochschule Freiburg im Breisgau with an Artist Diploma. I had spent two and a half years with Nicolet, and was offered a tenure track job in the St. Gallen orchestra without a second audition, which is exceptional. I was feeling lucky and very grateful.

I think it was around two years later that a colleague of mine in the orchestra told me about an opening at the Landeskonservatorium für Vorarlberg in Feldkirch, Austria, and asked if I would like to apply and have an interview for this position. I said I didn’t think so, because my plan was to leave St. Gallen and move on to a principal flute job somewhere. Then I reflected about it some more and I asked myself, “Well why not? Maybe in the meantime, I could teach here.” So I went to the interview and I got the job. This meant that, at the same time, I had two jobs, neither of which were full time: in the orchestra 2/3 and now the position teaching at the conservatory in Feldkirch, Austria, beginning with about ½ load. I started my teaching career when I was 27.

AH: That’s wild. I am 35 now and I’m just thinking about myself at that age.

EA: I was very lucky. I mean, what is success? I was just ready to go, had practiced for hours over years, I knew what I wanted and and I was in a certain way still a little naïve and blunt about the competition and the career as a musician. Until I got into the orchestra, everything just happened how I wanted it. I wanted to study with Rumpel, I wanted to study with Nicolet. I wanted an orchestra job. I just went for it. Completely, 100%. There was no doubt. I wanted all of the above.

AH: You just set your eyes on it and it happened. That is interesting.

EA: I have to say that in the orchestra it happened also that I got a chance to see who people are around me. When I went to my first rehearsal, which was not opera but operetta—

AH: It’s like a light opera.

EA: Yes. I remember that I was close to being disappointed because people were not as prepared or as focused as I expected. The conductor tried his best to be musically organized and get things done. There was not enough respect between players and conductor and vice versa, and today I know this happens anywhere. At the time it was surprising to me and I began to see that people are just people, including myself.

After two years in the orchestra, I began to feel a bit uncomfortable with the tight structure of that job. Literally, in the pit it was tight—not enough space, light or air. There was also very little freedom to go and do other projects, because you have to be on standby, even when you’re not on the rota.

AH: You get like a phone call and you have to go and play?

EA: Yes. Till 10 o’clock each morning, you have to be on call. If I wanted to take a different gig, which might last a whole week or so, I had to have somebody be standby for me. It was a pretty strict schedule, and you work evenings and weekends, of course. It was not really family friendly.

After two years, I kind of felt a drive to learn about my options and decide whether to enjoy the wonderful and positive sides of orchestral playing and stay, or quit and be a freelancer.

I decided to take a year off and that really helped me to get a clean mental slate, to understand how to think to be in the orchestra and always do my best. Regardless how people around you play or what their mood and attitude might be that day, you always do your best. You have to make sure that you can maintain a positive attitude. When there was a good atmosphere, I opened up and enjoyed what I got, the music and the collective experience, simply everything, and had a great experience. I had to learn to understand that you cannot expect the enthusiasm of an orchestra like the Swiss Youth Orchestra. (I joined it when I was 15, and everybody was so excited to play.) Does that all make sense to you? I had to kind of learn how can I be content and happy with what I wanted to do, playing in a professional orchestra every day, without getting frustrated.

AH: Were you teaching a lot during that time?

EA: No, I was teaching maybe two afternoons a week, not a lot. I did more later. My job in Feldkirch over the years became a full time job, so I worked 100% in the conservatory plus 2/3 in the orchestra for only a few years, plus taking all the extra offers for performing in Germany and France etc. Nevertheless, when I came to the United States, I still worked more here in Florida.

AH: I was about to ask you how it compared.

EA: For sure, more here in the US. Anyway, I stayed in the orchestra for 20 years.

With the job in Feldkirch, I also got opportunities to perform—together with two colleagues I founded ENIF, my contemporary music group. It started because of a famous piece of Boulez Le Marteau sans Maître—and I also got the chance to learn and perform his Sonatine for flute and piano.

AH: We talked about that actually, the Boulez.

EA: I played that sonata on about 10 concerts in a row. On the same program we played Boulez’s Le Marteau sans Maître for alto flute, guitar, viola, percussion and mezzo-soprano. It’s a wonderful piece. All Boulez is very virtuosic in terms of rhythm, but I don’t think it’s virtuosic overall. Of course it is fast but it is not like Taffanel Fantaisie sur Freischütz or something like that. It’s not that kind of virtuosity. It’s more like rhythmically really complicated and challenging, and this is what I like the most. I really like rhythmic virtuosity.

AH: You did it how many times you said in a row? 10 times in a row?

EA: Yes, in a row, meaning on 10 concerts over about six months. I took the risk to say yes to play it without knowing the piece yet because I wanted to be in Le Marteau and so I had to perform the Sonatine on the same program. I had never played either of them, but I said yes, because I wanted to have this Boulez experience with Oesterreichisches Ensemble für Neue Musik Salzburg

AH: You didn’t know what you were getting yourself into.

EA: Oh, yes, I knew! Hours of practicing and rehearsing! And the most important thing is that you have to have a great pianist. If you don’t have a pianist ready to play the Sonatine then you cannot do it because it is really even harder for the pianist than the flutist. I had a pianist, his name is Urs Egli, and I knew that he had already played it, so the two of us just had to put it together over many rehearsal hours….and that was it.

AH: I remember seeing the score the Boulez Sonatine when I was very young, like 19 or 20, and thinking I’d never be able to play it!

EA: I mean you are able to but as I mentioned: you need a pianist. Before you look at it, find a pianist. Out of this Boulez group, we founded an ensemble called ENIF. It was percussion, guitar and flute. We did big projects like El Cimarron by Hans Werner Henze—that’s a little opera, scored for singer, percussion, guitar, and flute. We did like to commission pieces, and we played a lot in Austria and Germany. We also recorded in the ORF studios quite a bit in Austria. We stopped playing together, once I moved to the US. Maybe we will start over again. I don’t know. We are still friends and I am in contact with the guitarist Dr. Günter Schneider who teaches at the Hochschule in Vienna, and the percussionist Hans-Peter Achberger, who plays with the Zurich Opera.

AH: They were both probably very busy.

EA: Yes, but we had a great time.

AH: It sounds like an interesting combination, percussion, flute and guitar. I’ve always wondered how that would go.

EA: That was the first ensemble I helped to found. The second group I was part of putting together was The Dorian Consort. The founding members were: Rudolph Lutz, a genius improviser, great organist, conductor and composer, based in St. Gallen; talented violinist Claudia Dora, whom I knew from our time in the Swiss Youth Orchestra; and myself. We wanted to play Bach cantatas, but we started by playing various composers who wrote in the Baroque style. After 6 years, we came to a fork in the road where a couple of our members wanted to go in a different direction and do more with Early Music instruments. They left the group and we got a new harpsichordist, Shalev Ad-El.

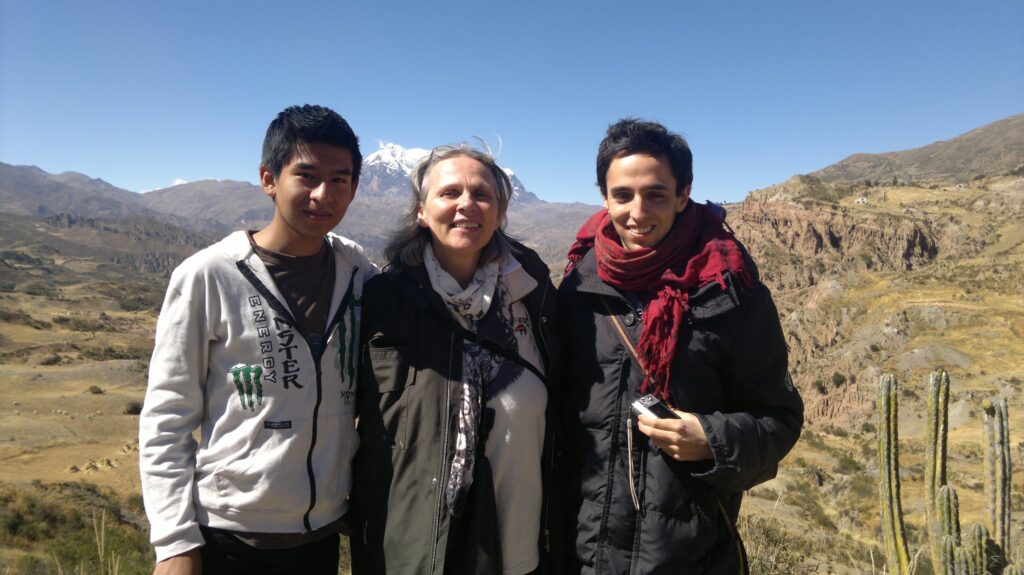

Our first international tour was to the US. Next was an invitation to visit China. We accepted and had very interesting and good tours, but after the China trip we had a long talk where we discussed what became a question of pivotal importance: did we want to go to western countries or did we want to go to less familiar places? We decided, since it was very fulfilling to play in China, where we met people eager to meet us, hear us and ask questions, that it would be more important to go to countries being really interested, curious and wanted to learn. One of our members had heard that there was a long term Swiss project in Bolivia. It was facilitated through the Swiss Culture Foundation Pro Helvetia. They supported the music scene there. The violin player agreed to contact the project leader and we decided this would be our next project.

AH: Wow, things came together – but I know, you went there many more times. How did this happen?

EA: November 2001 was my first trip to Bolivia, together with 3 members of The Dorian Consort. It was then that I was asked to return to teach all the flutists in La Paz. They wanted me for three months – I agreed to three weeks. The goal of my visits was to educate the students so they could become the teachers themselves later. That meant I needed to develop a plan over a few years/visits including all aspects of flute playing and repertoire and pedagogy. It was an important project to me. I wanted to have an exchange and not be the one who simply knows better. I wanted to treat everybody with respect for their knowledge. And I wanted to learn about their culture, their music and their flutes.

AH: You wanted to teach them how to teach.

EA: Yes, I felt I was supposed to share my knowledge. And I am very grateful Pro Helvetia supported the project for the Bolivian flute and classical music scene.

AH: That is an interesting point to make because a lot of people just go to play.

EA: Of course you play wherever you go. When musicians visit Bolivia, they very often go to see the incredibly beautiful landscape, Andean mountains, Lake Titicaca. As they pass through La Paz, they also teach a master class or play a recital. But when they arrive, they don’t know what the level is. Every flutist knows his own truth, but there are different possibilities to play the flute for each flutist. If you go to Bolivia and you tell the students and teachers what you found works for you, and then you leave and don’t return, you leave them behind feeling slightly confused, because you might have introduced a new idea to them, different from the visiting flutist the year before….

My thought was from the very beginning to give Bolivian flutists a foundation for their own kind of flute playing, including repertoire. Every time I went I brought music, even the most basic stuff. At the end of that time, we had our first Bolivian Flute Festival, which was a pedagogical meeting where other flute teachers from the country came, and it was really fantastic. It was a dream come true. The first flute festival was in La Paz, the second one was in Santa Cruz, the third one was a couple of years ago in Cochabamba, and the fourth one will be in one of the next years, in La Paz again. We rotate towns, connect regions and build community. Out of all of this work the Bolivian flutists, with Vivianne Asturizaga (also an FSU Alumni) as their first president, started their own Flute Association: Asociacion De Flautistas Bolivianos

AH: That is important. Do you see the same people? When you go, do they travel?

EA: Yes.

AH: Does everybody have flutes there? How do they acquire their instruments?

EA: They all have flutes but they are just not great instruments.

AH: That is how I wanted to put it, but I didn’t want to put it that way!

EA: My concern was not so much about that. I never really tried the flutes. I just tried to give them the technical background for the body awareness, the sound, the breathing and extended techniques, all of those parameters and foundations, but I never talk about flutes. I don’t want to do that. That is not my thing.

AH: No, no, I think the question really meant where were they getting their resources? Do they just rely on the senior teachers in the town to kind of pass along information or did they see videos, if at that time they had internet?

EA: Not really in Bolivia. They had internet at the time, but not at home and very slow.

AH: I am curious to know how the situation was when you arrived?

EA: First: Things were/are just not stable in Bolivia. Back then (2001/2002), there were not so many teachers and flute players there. They always were very welcoming and eager to learn. It was winter time—it’s on the other side of the Equator, so it was summer in North America and Europe. The rooms in the Conservatorio Plurinazional de Musica we were in were so cold! Then the political situation…I remember when we had a pedagogical meeting, we had to stay in the hallway of the building because the military was right outside and they used tear gas against demonstrators. We had to wait till they were gone, and when I went to my hotel, all the shades were down and they opened one to let me in. It was really dangerous at times, but I was never afraid.

Plurinational Conservatory of Music

(Conservatorio Plurinacional de Música).

Also the flute playing level was very different from what you might be used to. I wanted to teach them where they were – be with them. I wanted them to trust me – and it took several years till they understood: I would come back, I wanted to share, and I respect their level, their culture and them as people, I even wanted to know more about them and their history and traditions.

It is the same with my students at FSU. I am teaching them as much I can in their culture. If you come from Miami or you are a Native American, you are black or you come from a South American background, or any other background, then you have a different culture than an FSU or a Tallahassee person. Your background changes your culture. Respect culture. Support the culture of the person in front of you to make them stronger human beings. Make them aware of how good what they have is, and not just what they don’t have.

AH: Exactly.

EA: That is actually my credo.

AH: Let’s go back to The Dorian Consort and ENIF. That’s very interesting, that you’ve had one ensemble built around Baroque music, while the other specialized in very new music.

EA: Yes, I love both! As flutists, we have to stick to the repertoire we have. Of course, you could play the romantic repertoire, but at that time, people were not regularly transcribing pieces like today. We played mostly original literature.

You have to see it is different now than when I started playing with The Dorian Consort. Today, if you specialize in Baroque music, you go to early instruments. Meaning, most musicians who are into Baroque music, they are actually playing the Baroque flute.

When I had been in the orchestra a few years, in 1982, I got a wooden Boehm system flute from 1920. That is how I started playing Baroque music more authentically and when I really was getting into research about it. And not only me, the movement of authentic playing started right when I was still studying with Nicolet. The Early Music scene was slowly growing, and I found my place in it by playing my wooden flute a lot. Today, musicians have to do one or the other, because now it is well-known that Baroque music is one of a kind and unique. For me, it meant just to start doing it, listening to many different, also non-flute recordings, reading sources, trying things out and asking questions. I was exploring things that my teachers didn’t teach me. Of course Nicolet and Rumpel knew a lot regarding Baroque music, but they didn’t play how I played with the newer insights. In addition, Nicolet was always very much into contemporary music. I really liked this too, and I still like it today. I like the challenge of a new score and finding new things out, experimenting.

AH: It was almost like a new frontier, probably. I can imagine all of the research that was going on.

EA: Yes, because I was one of only a few players who were playing the wooden flute. When I came with my modern wooden flute, people were saying, oh, you cannot play this instrument, this is too soft, tuning is not good enough etc, but I said, yes, I can play it. Why not? So, I convinced them that that was something good to do. The wooden flute has a very warm and sweet sound, matches wonderful with the wood winds and also with the strings. Good intonation in the very end is a matter of flexibility, sensible ears and technique. I still own this flute from 1920 and it really taught me a lot, it helped me find my personal playing style.

AH: The flute from the ‘20s, what scale was it? Was it Baroque or…?

EA: No, no, a modern flute from 1920 with keys, tuning was 440 which is of course low for European tuning standards. The keys were not functioning that well but otherwise just a normal modern Boehm flute. It is a very nice instrument. I still have it.

AH: I was going to ask do you still have it. Did you ever work on it?

EA: Of course! With The Dorian Consort I always played on a wooden flute. That, of course, made a big difference because nobody played that way at the time. When we had our concerts, wooden flutes were always a pleasant surprise to the audience. The style we played in was similar to an Early Music group. When you hear our CDs, you don’t know we play on modern instruments. At our very beginning, we were always thinking that this is really the future, having modern instruments for playing Baroque music.

AH: I think so. The older instruments are there but we have to continue to move forward. It is the style that is needed.

EA: I think it needs both. Anyway, that was the second group that I founded and it was with them that I went to America, which as you will see, had a big influence on my career, too. When we talk about career moves, now we are already in the part when I started thinking that I wanted to quit the orchestra. Because, like I said in the beginning, there was not enough freedom. The schedule was too tight for me, not much musical freedom and so on.

It was then that Jeff Keesecker, the bassoon professor at FSU, was in the orchestra in St. Gallen for one semester. He had an exchange with our bassoon player who was himself an American. So I met Jeff Keesecker in my own orchestra and I liked his playing a lot. At the end of his time in St. Gallen, I asked him if he wanted to play with The Dorian Consort. He said yes, he would, and he came back a couple of times, and every time it was great fun. Then we did our first trip to the US. He invited us to Tallahassee and we played as guests of the town’s well known Artist Series.

You see, that is how it worked for me. I was just following my heart, doing what I liked to do. And because Keesecker and TDC liked to play together, as I said, we visited Tallahassee and he also invited me to stay on and teach a masterclass and give a recital at FSU during my visit. I had no clue what kind of high level school FSU is. I did not know about Charles DeLaney—how famous he was, how great his students are and what he had built at FSU over the years. I answered Keesecker, sure, I would teach and play, and that was good. I have fond memories about sitting in Charlie Delaney’s “magic circle” and observing his teaching. Surprisingly he talked about Switzerland and a poster of the Matterhorn was on the wall in his studio! We had something in common: he had studied in Switzerland. Overall we had a wonderful time. The second coincidence in Florida was that one of my students from Feldkirch was in Melbourne Beach. She was babysitting for half a year, and she had lessons with Nancy Clew. After I was done at Florida State University, I went down to see my student in Melbourne Beach for a couple of days and to meet Nancy Clew. That was about two years before I moved to the US. We had a great time together and we kept in touch. Finally, the Visiting Assistant Professor position at FSU opened up, and I was happy to come for a year as I always had been curious and interested in America.

AH: That is amazing. All of these chains of events, meeting Keesecker, coming for the concerts, meeting DeLaney and it is just very interesting how life plans out.

EA: Nancy Clew too, because she was very important. She told me that there was a job opening. She said to me, we want you to come to Florida. She wanted me to apply. Since some of the FSU colleagues had heard me in my FSU recital, had seen me teach a master class, they kind of knew me. Do you know what that means?

To say yes to the offer of a one year job was easy. I really wanted to come and experience an American college for a year. But then I had to think about whether I wanted to apply for the open tenure track position and maybe stay for good. That was a big decision. I said yes, because I really liked to play and to work with my colleagues. We have a fantastic working atmosphere, good discussions in committee work, and even went for bike rides on Saturdays in the early years! Being together was—and still is—fantastic! I think anybody would be lucky to have colleagues like I have. It is not that situations like mine don’t exist in Europe, but I just fit in completely with this group and I made my decision to stay mainly because of that.

AH: I like this! I’ve never really processed your life chain of events. It seems like it’s very intuitive. I know that you’ve always trusted your intuition and that you encourage others, like your students, to do that as well. I think that might be the reason why you have so many successful people coming from the studio who are starting projects on their own and doing different things because they follow their intuition. They just do it. I can think of handful of people who just do that. They put their eye on it.

EA: Yes. When I teach I try to help you get to know more who you are. My main goal is to help you to get closer to find out what your task in life is. We are not talking about your dream in a sense when you were 10 or 12 and you wanted to be a flight attendant or you want to be on stage because it seems glamorous. The question is: are you really a musician, passionate enough for an entire life, loving what you are doing…and if yes, what kind of a musician do you want to be? There are so many layers and facets to all you could be. There are not just two correct paths—teaching or playing in the orchestra. There are a big variety of other things you could do that might be more fulfilling for you even if they might not be that glamorous. I’m trying to take the glitter away. I get down to who you are a little more. I just offer you a hand as you slowly take your next steps into your very own career path.

AH: Yes, and studying with you is a different experience. I learned more than I have ever learned by myself.

EA: And it is not always easy.

AH: No. I laugh about it now.

EA: It’s a holistic teaching style.

AH: I liked that. It seems to me from your experience with the other teachers that you’ve never really had that yourself. From what I know, other people don’t teach like that. You never had teachers who taught in a holistic way.

EA: Oh, yes, of course. Rumpel: He talked about all kinds of things in his lessons. With him, in the end of a lesson, I often thought: I wanted to play this, I did not get to play that. He always made connections with other things, art, life, etc., and Nicolet did so, too, even more. Whenever he got back from a trip, he would either bring some stories or some books or some scores, a new piece. He read a lot of interesting books, not just about music, and he talked about them. He made reading suggestions to his students. My generation is just now adding mental training, enterpreneurship or the whole body awareness part of being a musician. Both of my teachers taught us a lot about focus and stage presence or breathing and posture. But I, in addition, am talking more about how a posture really even expresses something.

AH: Like body language?

EA: Yes. That is one thing. And as you start understanding more how to observe it, it changes your teaching. It will be more centered on the student, the human being. When you open up as a flute player – like opening your entire body for breathing, feeling your throat, finding your voice etc – you never entirely know what comes from it as you as a teacher help your student to explore. Opening means, of course, a richer sound, more overtones, great projection, a wide dynamic range, etc., but it also could bring up fear or insecurities. It might feel like taking a risk, having less control at first before you develop a good, solid foundation and work through these scary feelings. I am clearly teaching based on how I was taught, but then I am a different generation than my teachers, and take a few next steps. I just added a layer of Dynamic Integration (body awareness method developed from the Feldenkrais through Heinz and Ruth Grühling), awareness and mindfulness, as well as mental training and more.

AH: Dynamic Integration was a whole other project, speaking of projects!

EA: Yes. Body awareness came into my life when I was 15. I’d learned proper German with an actress, Wera Windel. She started talking about posture before she let me speak one word. I went there for 4 years and then, during my studies, Günter Rumpel sent me to an Alexander technique teacher, Noam Renen, which was very helpful too, and so I was already tuned in to that whole body thing very early.

Then I got my job in Feldkirch, and one of my students came and said she had met a very nice couple who would like to come and give a class in dynamic integration there. I said sure. I clearly remember that during the first weekend I had with them, the method completely convinced me: I explored and started understanding how to come from lying on the floor to sit on the floor without any effort. It showed me how you can use gravity, how to use the push from gravity, how to move without effort, and how important this is for your breathing and for balancing your body. It also taught me a few other things, like how to observe and be neutral and open instead of judgemental, presence and focus or that our biggest fear is fear of failure. From then on, I just kept going, and at one point I was offered education for teachers and I took it and I finished it before I came to live in Florida.

Of course, I wanted to teach it at FSU and I created a class where I teach all the students— everybody who wants to enroll from the College of Music can attend. It teaches students not to forget their body in their busy daily life. They need to understand that the body is the first focus in their daily practice to be able to play an instrument, to be able to play music and to be able to make your career progress. Dynamic integration is still a big part of my life today.

Pauses…thinks….

Then I started these flute festivals at FSU.

AH: Did the syrinx festival come before that or did you do that before?

EA: Yes, the syrinx Association Festival started in 2001.

AH: How did that start?

EA: At that time nobody did festivals, master classes, etc., that much, as this idea was not established yet. I hosted yearly master classes at my school in Feldkirch, and I was completely doing it by myself at first. Why did I do that? It’s the same reason why I do it in Tallahassee. Feldkirch is a small town in Austria and Tallahassee is a small town in America. Would you agree with that?

AH: Totally.

EA: We are a kind of isolated as flutists, and we don’t know what’s out there. I felt the need to bring people into my school in order to give my students a horizon beyond Tallahassee.

AH: I agree.

EA: That is one of my main reasons why I do these things. The second one has to do with getting my name out for recruiting as well as for my students for their career—not many people knew me. So, to invite other flutists to my home and let them experience what I am doing is as good as going out to NFA or to other schools, branching out and meeting them there.

AH: Of course, even better.

EA: Yes, I think both ways are important. I also wanted to build even more community in the FSU College of Music. So in the last 19 years, I did 2 Flute festivals, started the FSU Woodwind Days and last year hosted the newest version, Flute Summit – the 21. Century musician, with an even bigger idea, inviting guest flutists, who also have other skills like an entrepreneur, medical doctor, mindful teaching and learning instructor or specialists in body awarness, pedagogy or flute choir. I had two topics for the the first two flute festivals. The second one was a holistic topic, Flute Health and Healing from the Americas and I did it together with Dr. Ben Coen from the Ethnomusicology department. The first flute festival, Different Generations, happened thanks to Charles DeLaney; he and his alumni were so generous to me from the very beginning. I felt very welcomed, so I wanted them to be able to come to Tallahassee to see their teacher again and in addition start to build a connection between DeLaney times and this new era with my teaching and my students.

AH: I can tell that. I think people can tell that too, that you really want that connection and that there is a very strong lineage.

EA: Right.

AH: I always think Americans are not like that to some extent, but the fact that you are from Europe and you have a long heritage where America is relatively young. I think you bring that with you, that lineage.

EA: Yes. I think that is true.

AH: It is really nice. And the syrinx festival, do you still go back every year for the syrinx?

EA: Yes. Every year, end of September and beginning of October, we have our festival.

AH: I was looking at the website before we started to talk. It seems like it is very active.

EA: Yes, we have a festival and it is very small. I think I really like that it is small. It is great to have conventions like NFA, which is the biggest in the world. It is also nice to have something like a small family where you know each other and…I don’t know….maybe can bond in a different way?

AH: And you can be personal.

EA: Yes, and you are going to the sessions together, you are experiencing this event together. It’s a completely different approach and we don’t want to become bigger. We are original, somehow. For our 10th anniversary, we went big. We invited Project Trio to be our guests and organized a tour for them in Austria. We wanted to do something special—our goal was to give a gift to other people as we celebrated our anniversary. But we don’t want to become bigger because of that. We’ve got a small gathering and we want to have an exchange between teachers. The main reason why I founded syrinx was because I felt that teachers were lonely and they needed a platform where they could meet and talk.

AH: I like that. I’ve never quite understood fully what you were doing but it makes perfect sense.

EA: Yes, that is the main reason. There is always a masterclass, like we had with Jasmine Choi a couple of years ago. She was teaching two masterclasses to students, open to everybody from everywhere. We also want to educate new teachers, so we also have a pedagogical event. In this same year it featured Raphael Leone from the Vienna Symphony. He is a good and experienced teacher, tenured at the University in Vienna. He did educate flute teachers, and he talked about romantic repertoire for middle schoolers. It’s an easy repertoire, not the difficult things. He taught a few kids for people to see his pedagogical approach, and then we had a discussion. We always have a couple of exhibitors who come to show instruments and music, sometimes a repair person. It’s just a very small exhibition. That way, everybody is happy.

This is our fall event. Then in spring, we have a workshop where we work together with music schools in the area and invite guests. It is important to us to collaborate with the musicians and other organizations in the area. We have one gathering where members can talk about literature or just have an exchange. Then we go to concerts together in the area. In Liechtenstein, you can go for free to certain events or to rehearsals.

It is small, but it is nice. We have a small board and the meetings are always great and fun. I am very happy to now have a successor in the association. Giovanni Fanti is elected the president and I am the vice-president. We have 2 other board members from the area and one from Switzerland as well as one from Innsbruck. Her name is Dr. Petra Music and she studied in America with Dr. Jonathan Keeble. This is a nice coincidence. Everything comes together … Yes, I think everybody likes it.

AH: And I see how you take that model of community and bring it to FSU, and you have a bunch of different students from everywhere but it is still a small town. It is almost amplified because you have all of these students’ experiences and you have these master teachers that you bring in and you work with. It is really kind of the same but it is also really different, I think.

EA: The Flute Association at FSU was not my idea. There was an arts administration student and a flute student, and the two of them together were starting it in my second year. It was their initiative and they just got it off the ground. They asked me to be their advisor, and of course I shared with them what I knew. Over the next 17 years it developed into a very successful organization! I think such sharing also serves as entrepreneurship education for my students. I can suggest things, and I can be a role model for them. They are the board members, the president or whatever, so they learn a whole lot about the business of entrepreneurship, organization, communication, how to raise funds, all of that necessary stuff. Learning how to build community and how to set goals is so important. They find out where their weaknesses are and where their strengths are. Since it is under the umbrella of the school, I am responsible for everything. If a mistake is made, it is me who is responsible. They have a nice playground!

AH: That is a good way to put it. I felt that way, especially with the financial side. I am learning how to write a grant, I am fundraising and I never knew these things were possible before that.

EA: Yes, that is one thing—learning through the Association work—and the other thing is experiencing skills through the teaching assistantship. When I see a prospective student and they ask about the assistantship, I let them know, what that means right away: yes, you are going to teach 3 to 5 students depending on how big the number of students in the studio is in that fall, but then you’ll do a lot more work. Do not compare with the clarinets or the bassoons or other schools, we will do a whole lot more. But you have to understand how beneficial it is. You will be doing what you do at a professional job later. The transition into professional life is going to be much easier… It prepares them 99% to the best possibility for what they do after graduation, because each TA has an extra job, either at the library or being in charge of the flute choir, attendance, different things. They have responsibilities, again under the umbrella of the school and with my (now our – we have a additional flute professor, Dr. Karen Large since 2018) guidance. Since we know they do more, every Tuesday we have a meeting lasting 75 to 90 minutes. They work more, they get more of our expertise, our experience and our advice. And it goes from organizational stuff to planning, to pedagogy, to repertoire, to problem solving and, and, and…

AH: You know that is something I really enjoyed about being at FSU. I have never had a specific pedagogy class for flute, and you have those degrees in Switzerland. Like you said, that degree doesn’t really exist here in America. And yet, it is interesting because in almost every class, I would teach. I think that really opened up my eyes on the methodologies of teaching. It was just more than somebody coming in and you telling him how to play.

EA: What you said is completely right. What I created is the dynamic integration class for body awareness. I created a flute pedagogy class so that my students know how to teach and so that I don’t have to oversee so much during the school year. I don’t have to worry about that really because they learnt how to teach. And the third thing I added is the Baroque flute and I have to say that I took it from Charles DeLaney. I really think, being a beginner again on the Baroque flute and/or the recorder, (you may take it for just one semester) is really, really great. Then of course for the historical aspect, learning to research, but also for body awareness through Baroque Dance—it is so beneficial for all your flute playing. Having a historical instrument for one semester in your hands, what a chance! You are gaining invaluable experience and it really helps for the future regardless of what you do later. Many of my graduate students take the advanced Baroque flute class and the Baroque Ensemble (with other instruments) and keep developing their playing on period instruments after graduation. I also put together and added a Piccolo class, and finally 2 years ago a Low Flutes Class. They alternate and are open to all students, undergrads and grads.

Those are the things that I created in addition to flute days, flute choir days, flute festivals and woodwind days.

AH: It’s so much stuff.

EA: Then when all my students started being really good at Baroque flute, we founded Traverso Colore Baroque flute ensemble!

AH: That’s funny.

EA: We have an educational kind of touch. We want to help people understand historical flute and Baroque music in a different way, so we did a couple of educational events and we played at the Florida and NFA conventions. We have 6 members; we are having great fun together. A couple of members are transcribing music really well, so we have also made the Baroque flute repertoire bigger, with pieces that work for modern flute ensembles, too. This year, we started publishing with ALRY: our own Traverso Colore Collection, Vol. 1- 5 and we were awarded to be a finalist in the newly published music competition!

AH: That is nice. You take pieces and you fit them for the ensemble.

EA: Yes. We did some Bolivian Baroque music; we did some Renaissance Choral Music, some Bach and more. We choose different pieces we like, and one of the group transcribes them and we really have fun playing them.

AH: Have you thought about commissioning something for…?

EA: No, we don’t play contemporary music so far.

AH: That was what I was about to say. Mostly it’s just transcriptions from older things?

EA: Yes. Like historical stuff. Sometimes we also go on tour in smaller groups or we have a harpsichord player like Shalev Ad-El with us. When we play with him, we have a program with flute sonatas and ensemble music. We had another program where everybody played one of the 12 Telemann Fantasies, plus ensemble music. Whatever comes up, it is nice to have different program possibilities. Our latest project is the recording of a CD to be coming out September 2020 with our own transcriptions!

AH: That is really interesting. The progression fits into our little chronological graphic to show all of the things and how they lead into one each other.

EA: Yes. Should I tell you about my hobby or do you have some other questions?

AH: I was going to ask you if you have a piece of advice for aspiring young professionals in the flute world.

EA: Follow your own path. Do what you truly love and enjoy. Remember music and arts is the best education you can get and you can give and share yourself through teaching and performing. Have the courage to take risks – but also keep being grounded: Feel your feet and breathe! And to end, remember Carl Jung’s very wise words:

I am not what happened to me

I am what I choose to become

About Eva Amsler

After 20 years of orchestra playing in Switzerland and serving on the faculty of the Vorarlberg State Conservatory of Music in Feldkirch, Austria, Eva Amsler is since 2001 Professor of Flute at Florida State University. In this position she is also teaching Flute Pedagogy, Baroque Flute, Dynamic Integration and directs the Flute Graduate Ensemble.

As pioneer on authentic interpretation of Baroque Music on modern flute and advocate of New Music (including Piccolo, Alto and Bassflute) she enjoys a worldwide career as a performer and teacher. Eva Amsler tours and performs with The Dorian Consort and Shalev Ad-El, harpsichord. She loves all sorts of Chamber settings enjoys being a soloist and is Principal Flutist in the Tallahassee Symphony Orchestra. She has appeared at concert venues nationally and internationally, including Carnegie Hall, and Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., the Belk Theatre in Charlotte during the NFA Convention 2011. Among others she was invited to be part of the European Flute Festivals such as the German Flute fest, the Spanish Convention and Flautando 2019, Switzerland, and in South America, the Peruvian Flute Festival and the Bolivian Flute Convention La Paz, Bolivia. She also regularly holds master classes in Europe (for example MUK Vienna, Austria), the United States (for example Julliard School of Music), South America, and Asia. Eva Amsler’s summer classes in Arosa, Switzerland and Tuscany, Italy are well known and liked as a special time for deep and holistic learning as a human being, musician and flutist.

As founder and past president of the European Flute Association “syrinx” (Society for Sponsorship and continuing Education of Flutists) she was responsible for programming the yearly Flötenfest for 15 years. With Traverso Colore she is, together with FSU Alumni, enjoying Baroque flute performances and educational events. She regularly performs on Baroque flute with Shalev Ad-El, harpsichord and with Bach Parley Tallahassee, FL and a few ensembles in Europe (for example Ensemble Corund, Switzerland). Her CD recordings have been released on the ‘ambitus’ and Cavalli labels.

Currently she serves on the Board of the National Flute Association and is a member of the NFA International Committee. She has hosted Flute Festivals at Florida State University, including “Different Generations”, “Flute – Health and Healing from the Americas”, “Baroque Day”, “Wood Wind Days”, “Flute Summit 2019 – the 21st Century Musician” and more.

Amsler’s teachers include Günter Rumpel, Aurèle Nicolet and André Jaunet. She loves Miksang Photography and to walk on the ocean, hike in the mountains or hang out with family, friends and colleagues.

Liebe Eva

Ein fantastisches Interview!

So viele Ein-Sichten,

welch ein Reichtum an Wegen und Initiativen!

Respekt, Respekt!

Jetzt gratuliere ich auch zu deinem 20- Jahre- Jubiläum.

Deine ehemalige Mit- Lerche und derzeitiger Zugvogel

Eugen

Eugen

[…] Excerpted from A Conversation with Eva Amsler […]