The Cuban Charanga Flute Evolution through Danzón Improvisations of Antonio Arcaño, Jose Fajardo, Eduardo “Richard” Egües, and Orlando “Maraca” Valle

During the nineteenth century, Cuban popular music became the conduit through which sub-Saharan rhythmic elements were first codified within the context of European (‘Western’) music theory[1]. The flute characterizes the sound of the typical Charanga instrumental ensemble or orquesta; together they have become integral parts of the history of artistry and music in Cuba. From the turn of the twentieth century to the 1950s, the danzón and its dance ensembles featuring the flute occupied a prominent position in the international scene, leading to dance styles as the mambo, the chachachá, and the pachanga. However, the danzón’s popularity decreased amongst these new genres, and recently the flute has slowly disappeared from Cuba’s musical environment[2]. Therefore, it is important to remember the developments in Cuban charanga flute performance, it’s influential innovators, and explore how it can continue to evolve.

This typical danzón form was a Rondó (ABACAD) and consisted of: A = introductory paseo section (8 measures), B/C = verses, and D = extended open montuno section with faster tempi, increased percussio, flute improvisations, and the intention to motivate people to dance.

The charanga orquesta usually consisted of flute, piano, violins, double bass and/or cello, vocals or coro singers (typically male), and percussion (clave, timbales/paila, guiro, with congas later added). The percussionists played a composite rhythmic foundation, the lower strings played a bass line ostinato or guajeo, the violins played the paseo melody or inner-voice melodic material, the piano occupied multiple roles including realized chords and countermelodies, the vocalists could sing the main verse melody or enter during the final montuno section, and the flute played ornamented melodies and improvisations. Originally this instrument was a transverse wooden flute, arriving in Cuba from eighteenth-century France[3]. Today, charanga flutists either use the modern Boehm-system or the nineteenth-century, five-key, French simple-system flute.

The typical flute style consisted of eighteenth-century ornamentation from late baroque/early classical flute traditions (turns, trills, mordents, and grace notes embellishing melodic content), melodic injections in the flute’s high tessitura, and articulation full of clarity and percussive effect. The style of improvisation was far more arpeggiated than in jazz, with a call-and-response structure that created a special kind of relationship between soloist and ensemble[4]. The harmonic language is diatonic and classical in nature with a regular alternation of tonic and dominant harmony (II-V7-I); chromaticism is more typical of the jazz tradition.

Complex rhythmic counterpoint is the overriding characteristic that defines charanga flute solos and the language of Cuban flute playing, based in African rhythmic traditions[5]. The foundation of all Cuban dance music is the clave rhythmic cell, found in the music of son and rumba (3+2 or 2+3). Flute solos must adhere to the clave pattern and fit into the unrelenting structure it provides to accomplish the rhythmic accuracy and contrapuntal complexity. Particular rhythms (habanera, tresillo, cinquillo, baqueteo) interlock well with the clave foundation, creating a complex rhythmic counterpoint with the rest of the ensemble.

Antonio Arcaño (1911-1994) was born in Havana and became a professional musician at the age of fifteen. In 1937, he started his own group, Arcaño y sus Maravillas and broadcast regularly on Cuban radio from the late 1930s through to the 1950s. Arcaño’s main legacy as a flute player is in his widening of the improvisatory role of the flute in the charanga ensemble. He represented a transitional stage between the very early florear style of melodic ornamentation and the more montunear groove-orientated soloing on the mambo, son and chachachá during the 1940s and 1950s. His playing usually incorporated wide vibrato and extensive use of rubato on composed melodic material.

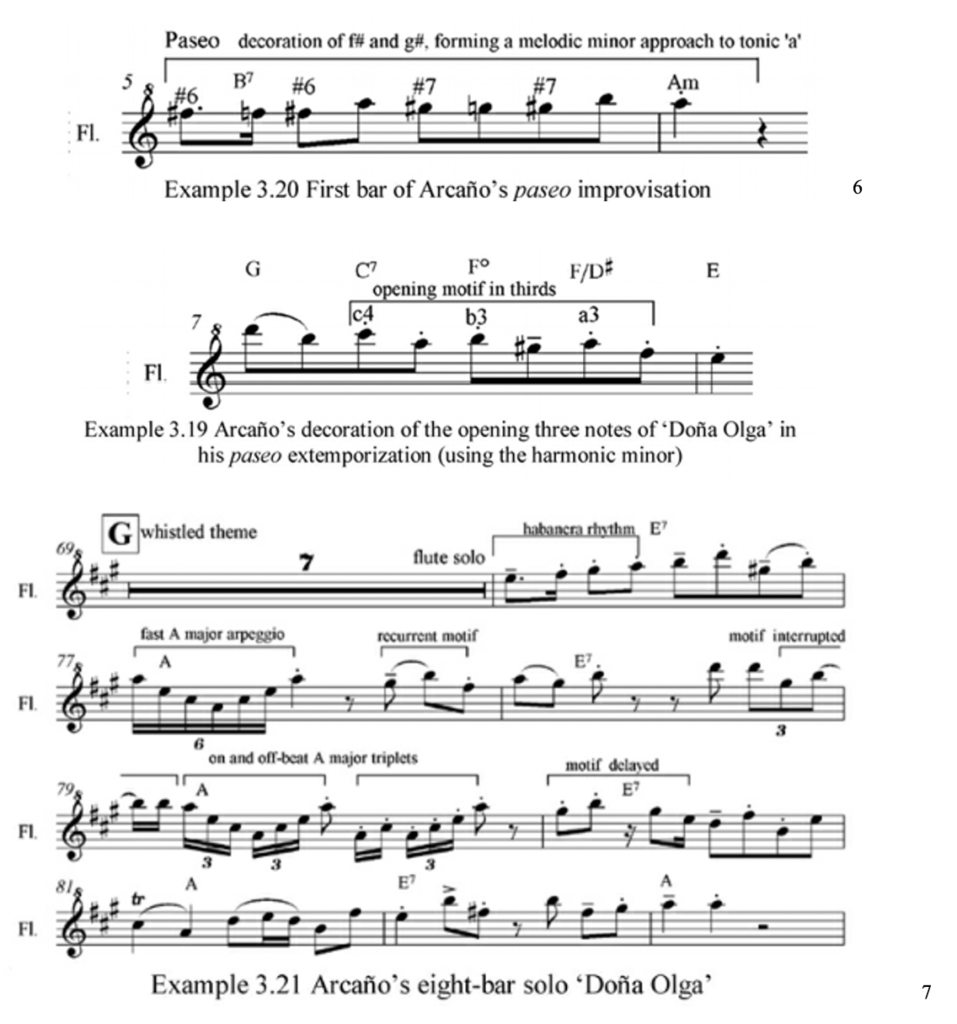

In the three-bar paseo (mm. 5-7) of ‘Doña Olga,’ Arcaño decorates rising (chromatic neighbor tones) and falling (use of 3rds) figures of the A minor melodic and harmonic scales. In the montuno section, Arcaño’s eight-bar solo introduces A major arpeggios (closely related to these previous A minor chord embellishments) in sextuplet forms and uses other motivic material (habanera rhythms and g#3-b3-f#3 patterns) from previously composed parts of the arrangement. In summary, Arcaño’s style is one based on romantic interpretation, melodic decoration, and some sequential patterning.

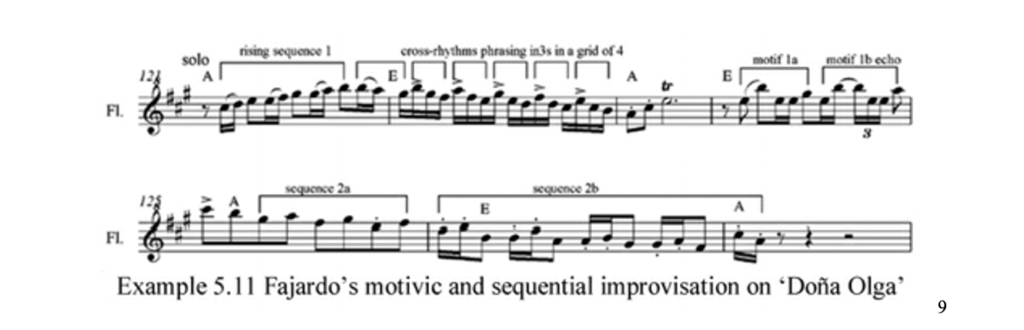

José Antonio Fajardo (1919-2001) set up his own charanga orquesta, Fajardo y sus Estrellas, in 1949 after a two-year stint in Arcaño’s Maravillas. Known as a virtuoso flute improviser, composer, arranger and band leader, Fajardo’s contribution to Cuban popular music has been immense both within Cuba and internationally. Eventually Fajardo moved to New York in 1961 and brought the charanga tradition to a larger audience in New York City.[8] Regarding the interpretation of composed material, Fajardo does indeed continue Arcaño’s legacy in terms of his use of Western Art romantic expressive devices, yet with more motivic development and sequential ideas.

His solo also contains fast rising sequences, cross-rhythms, call and response motifs and other diatonic patterns that form part of the stylistic vocabulary of the charanga of the 1950s and early 1960s. Fajardo surrounds structural melodic notes and motifs with sequential patterns. His solos are never made up of a string of meaningless sequences and runs.

Eduardo ‘Richard’ Egües Martínez (1923-2006) came to fame in Orquesta Aragón. He helped the ensemble rise to national fame in the latter half of the 1950s. Egües, initially classically trained, played ahead of orchestra in a more soloistic, virtuosic, and assertive style with florid, ornamental, exciting, and inventive. In his style, sequential and motivic development play a central role in charanga flute improvisation.

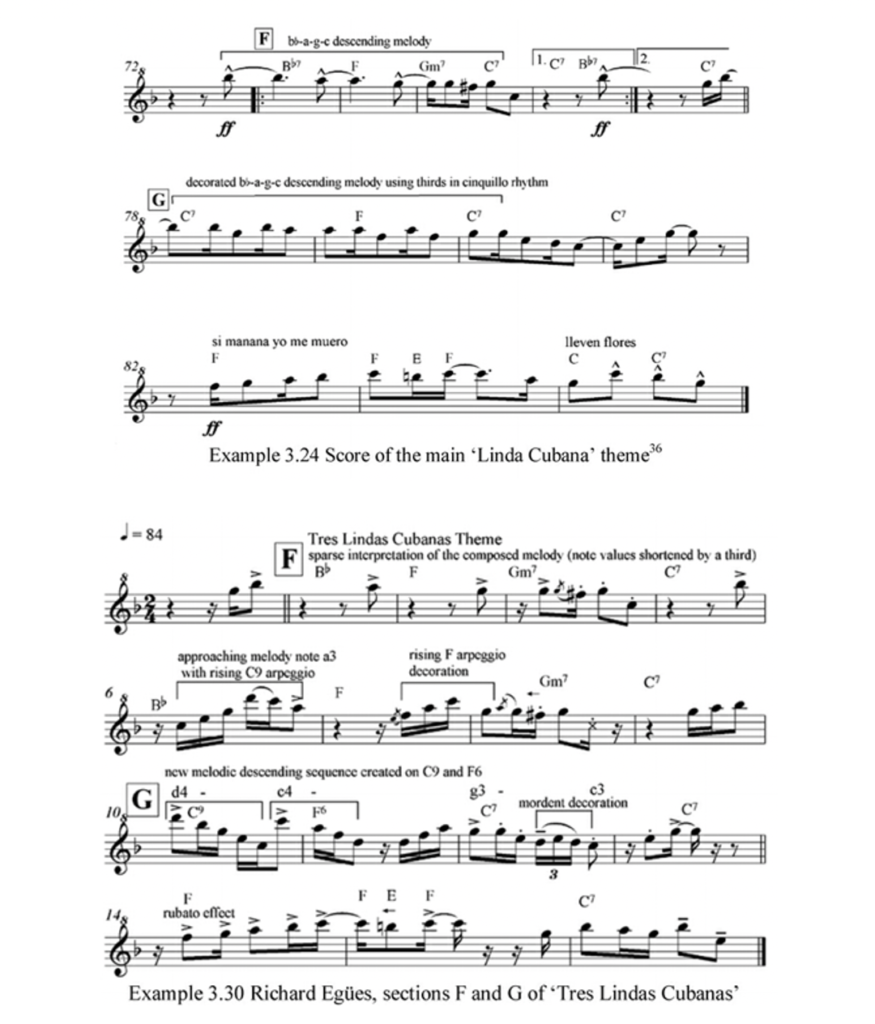

In the beginning melody of ‘Tres Lindas Cubanas’ Egües approaches structural notes using wide intervallic decorations, neighbor notes, acciaccaturas, and sequencing. While mm. 1-4 outline the original theme with minor subtleties, the restatement in mm. 5-8 contains rising arpeggios that descend to approach the melodic notes a3 (m.6) and g3 (m. 8). Arpeggiated decoration continues in mm. 10-12 with an asymmetrical cross rhythm in mm. 10-11.

Orlando “Maraca” Valle, one of Cuba’s top flute players, was born into a family of musicians in Havana, Cuba, in September of 1966. He eventually formed his own group in 1999, Maraca & Otra Visión[10]. His style is progressive and scintillating while still maintaining clear links to the past, from traditional Cuban forms, to Latin Jazz.

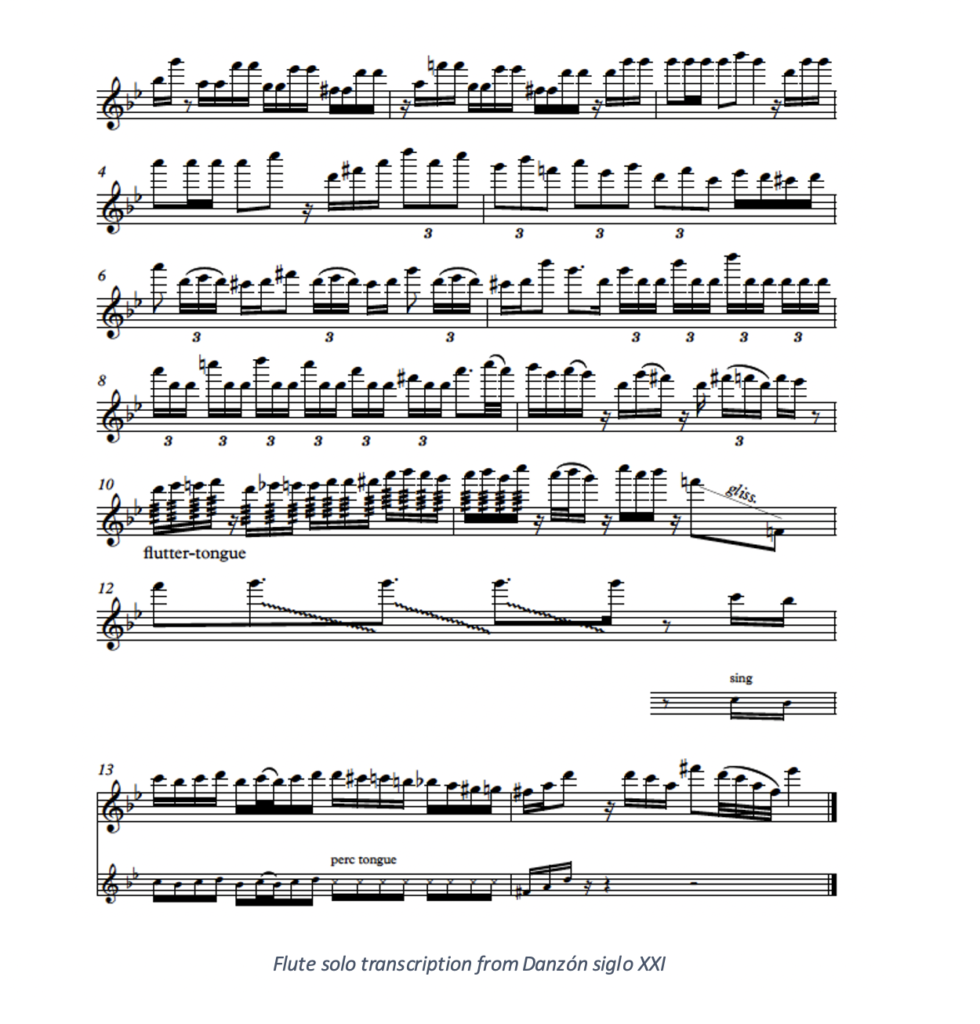

In Danzón siglo XXI (21st-century Danzón), Maraca performs with a more hybrid Latin-style like Dave Valentin or Nestor Torres. In just a short excerpt of an extended solo, there are moments of dynamic expression, frenetic rhythmic energy, virtuosic articulations, and free ornamentation. Complex rhythms include cross-rhythms, irregular rhythms, and rubato that can only be approximated with Western notation. The melodic material uses a sustained high tessitura range, a great deal of sequencing, and extended techniques (flutter tonguing, singing & playing). Following a long line of innovative Cuban flutists, Maraca continues another chapter in the virtuosity, complexity, and creativity of the charanga flute evolution.

[1] David Peñalosa, The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins, 81.

[2] Javier Zalba, The Flute Soneando, 14.

[3] Martha Councell-Vargas. “Towards a Cuba Flutistry: An Exploration of the Charanga Flute Tradition.” The Flutist Quarterly, 22–28.

[4] Ibid[.], 24-26

[5] Ibid[.], 26

[6] Ibid[.]

[7] Ibid[.]

[8] Ibid[.]

[9] Ibid[.]

[10] Nate Cavalieri. Orlando ‘Maraca’ Valle: Biography, Albums, Streaming Links, AllMusic, www.allmusic.com/artist/orlando-maraca-valle-mn000048114

Bibliography

Peñalosa, David “The Clave Matrix: Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins.” The Clave Matrix: Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins, Bembe Books, 2012, p. 81.

Zalba, Javier. “Historical Review.” Flute Soneando: The Flute in Cuban Popular Music, Alfred Music, 2015, pp. 14.

Councell-Vargas, Martha. “Towards a Cuba Flutistry: An Exploration of the Charanga Flute Tradition.” The Flutist Quarterly, 2013, pp. 22–28.

Miller, Sue. Cuban Flute Style: Interpretation and Improvisation. Scarecrow Press, 2014.

Cavalieri, Nate. “Orlando ‘Maraca’ Valle: Biography, Albums, Streaming Links.” AllMusic, www.allmusic.com/artist/orlando-maraca-valle-mn0000481147.

About Ceylon Mitchell II

Ceylon Mitchell II is a flutist, arts entrepreneur, educator, and arts advocate in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. His mission is keeping classical music alive, authentic, and accessible. Originally from Anchorage, Alaska, he has earned a Master of Music Education degree from Boston University and a Master of Music Performance degree from the University of Maryland, in addition to a Graduate Certificate in Multimedia Journalism. Ceylon is currently a Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA) student under the tutelage of Dr. Sarah Frisof at the University of Maryland. Recent achievements include the Strathmore Artist in Residence Class of 2021, a 2018 Prince George’s County Forty UNDER 40 Award in Arts & Humanities, and a 2019 Prince George’s Arts and Humanities Council Artist Fellowship Grant. As part of the grant, Ceylon presented a series performances exploring Western-European classical flute music in the Latin American countries of Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Brazil.

An active freelance flutist and chamber musician, Ceylon is committed to promoting traditionally marginalized communities, especially those from Black and Latinx identities. He is also the co-founder, and flutist of Potomac Winds, a chamber music collective. As a music educator, Ceylon maintains a private studio in Maryland and serves as the Potomac Valley Youth Orchestra flute choir conductor. He previously served as a teaching artist with the Boston Flute Academy and as the director of the Boston University Flute Ensemble.

Ceylon supports performing artists and arts organizations with digital media production and marketing consulting as the owner and founder of M3 | Mitchell Media & Marketing, LLC. Tailored services include photography, videography, and digital media marketing. Previous clients include Americans for the Arts, International Contemporary Ensemble, The New School, Quinteto Latino, and numerous individual artists. Ceylon seeks to equip and empower his fellow performing artists for artistic and marketing success in a 21st-century landscape. He is also an active arts advocate in the D.C. area, serving as a board member of the Arts Administrators of Color Network, a junior board member of Washington Performing Arts, a Professional Member of the Recording Academy Washington D.C. Chapter, and Arts Advocates Network of Maryland (AAMN) member with Maryland Citizens for the Arts.

Mentors, past and present, include Dr. Sarah Frisof, Dr. Saïs Kamalidiin, Ms. Janese Sampson, Professor Leah Arsenault, Professor Linda Toote, Dr. Carmen Lemoine, and Sharon Nowak. Additionally, Ceylon has performed in masterclasses for Aaron Goldman, Marina Piccinini, Sir James Galway, Paul Edmund-Davies, Trevor Wye, and Marianne Gedigian.