How do we open our mouths quickly and efficiently to get in the air we need as flutists? Where does this movement come from? How can we cooperate with our body’s design instead of fighting against it?

Why the mouth, anyway?

Why do we breathe in through the mouth for flute playing? I have read Breath by James Nester multiple times and there is a ton of evidence pointing to the overwhelming importance of nose breathing for overall health and wellness, but we are taught to breathe in through our mouth as flutists. Why do we do this? 1) It’s faster because the passageway is shorter and wider, 2) there is less resistance, and 3) we can get more air in through the mouth than through the nose in the same amount of time. There’s also an issue about how much noise is made. Take a very fast, aggressive inhalation through your nose and you’ll hear the very audible sniff. If you breathe in slowly and evenly through the nose, you’ll discover that there’s no noise! But it takes much too long for our flute purposes. Interesting exercise though to do some long tones and warmups while nose breathing. You may discover that you do interesting things with your tongue inside your mouth that you were unaware of before breathing in purposely through the nose. There are physical reasons for the gaspy inhalations that happen when breathing in through the mouth, but that will not be addressed in this article.

How does the jaw move?

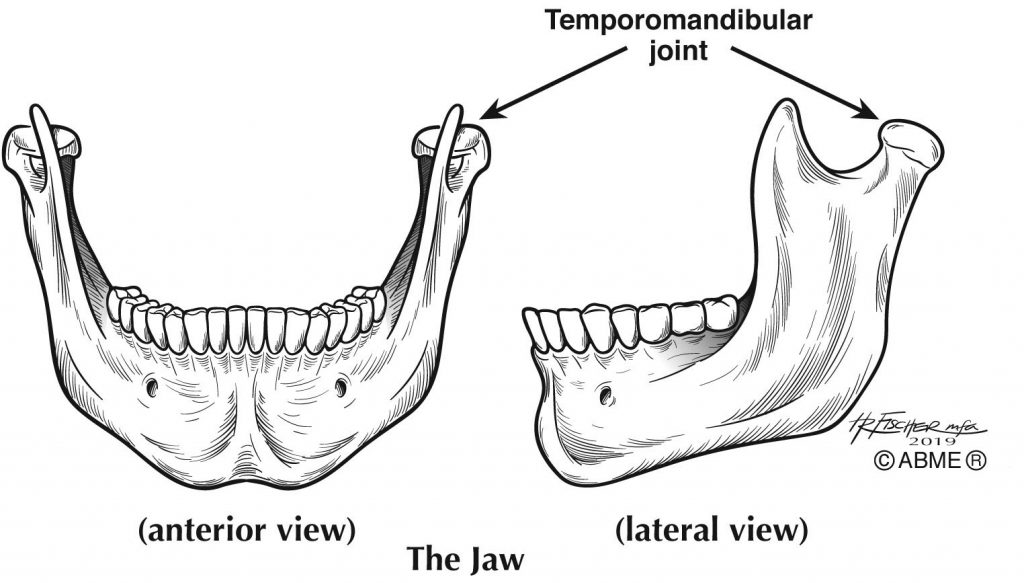

First, let’s be crystal clear about the structure we’re discussing. Orthodontists often talk about upper and lower jaws in terms of where the teeth hook in and what they need to address to fix the mechanics of the bite. This upper jaw is called the maxilla and it’s actually one of the facial bones. The top teeth hook in to the maxilla, but the maxilla doesn’t move independently from the rest of your skull. The bottom jaw is called the mandible, where the lower teeth hook it. This is the structure that we are interested in. The mandible attaches to the temporal bone, which is part of the skull, at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). You have 2 TMJs, one on either side. There is an articular disc, a piece of connective tissue, in between the two bony attachments. The joint is both a hinge and gliding joint is perhaps the most often used joint in the body.

Put your index finger in the space in front of your ear holes and then move down slightly onto bone. Gently open and close your mouth and you should feel movement here.

Students will often tell me that their dentist says that they have “TMJ.” Well, yes, everyone has 2 TMJs! What they mean is that they have been diagnosed with TMD (temporomandibular dysfunction or disorder) which can include symptoms of pain, pain with chewing, and clicking/popping of the joint. This condition needs to be diagnosed by a medical professional. If you are having any of these symptoms, get to your dentist right away because damage to the articular disc is big deal and you want to prevent that at all cost. For many, having a custom fit bite-guard from the dentist to wear at night helps eliminate the grinding of teeth and helps improve symptoms.

Where are the jaw closers?

Here is a link to a youtube video that shows both the masseter and the temporalis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ME5hPcy8bq4

The masseter is one of the strongest muscles in your body if you consider the amount of force it can produce relative to its size. Chewing and grinding up food is important for survival. The masseter runs from the cheekbone down to the back of the mandible and you have one on each side. If you clench your teeth together and put your hands on the sides of your face (cheekbones to jaw), you’ll feel the tension there! This is the face that Kevin makes often in the Home Alone movies (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zlu7S8dUUBY). On many people, these muscles are very tight and uncomfortable. You can do some self massage by gently applying pressure in a circular motion with your thumbs or fingers.

The second jaw closer is the temporalis. It is located on the temporal bone and runs underneath the cheek bone to attach onto the coronoid process of the jaw. Place your hands gently on the side of head, covering your temples, and clench your teeth. You should feel the temporalis contracting. Feeling the coronoid process on the other end of the temporalis is a bit trickier. Start by finding the middle of your cheekbone and then dropping down a bit. Gently open and close your mouth. When your mouth is open, you should feel a bony, denser texture move into your fingers. If you don’t feel anything, then you’re probably not in the right spot. Try moving down a bit more or over to a side. Keep opening and closing and moving your fingers until you find it.

Let it go…

The TMJs are the only joints that we are consciously holding closed much of the day. At rest, there should be some space between top and bottom teeth. Many of us hold tension generally in the masseter and temporalis muscles. We clench our teeth and end up with tension headaches on the side of our head, grind our teeth or have pain/tension/discomfort in the masseter area. For flute playing, consider this. Clench your jaw on purpose, which is engaging both masseter and temporalis on each side. Gently relax those muscles. Voilà, your mouth is open and you allowed gravity to do that for you instead of recruiting other muscle groups to open your mouth.

Where are the jaw openers?

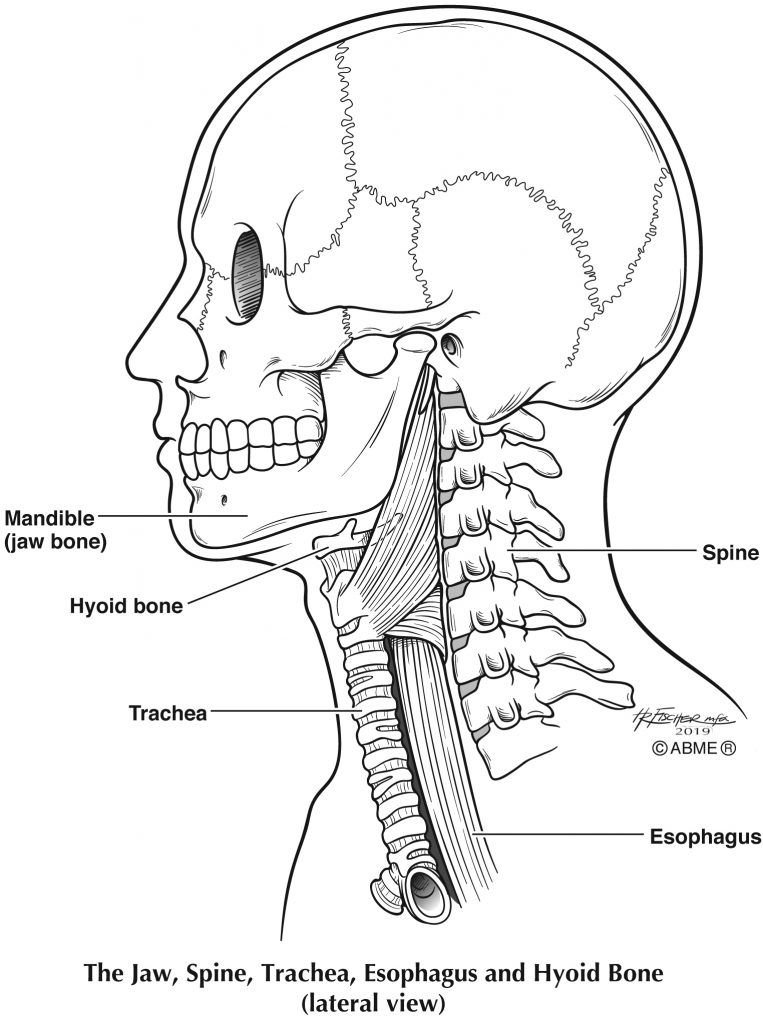

The openers include the digastric muscles, the suprahyoids and the infrahyoids, and they live underneath the mandible. The digastric (https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/digastric-muscle) is a cool muscle, attaching from temporal bone of the skull, running through a little sling that suspends the hyoid bone, and then attaching to the front of the jaw. The suprahyoids connect the hyoid bone to structures uphill, while the infrahyoids connect the hyoid to structures downhill. This youtube video shows both suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles groups, starting around 23 seconds – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELs0nWAHfEQ

To feel these muscles engage, place your hands under your chin. With your mouth closed, press your tongue up into the roof of your mouth quite aggressively. You’ll feel tension in the jaw openers under your hands. Another option is to have your hands in the same starting place, under your chin with mouth closed. Then try to open your mouth, but resist the movement with your hands. Again, you’ll feel tension in the jaw openers.

Which are the stronger group of muscles – the openers or the closers?

Definitely the closers. In addition to chewing and grinding food, mouth closing is protective. Maintaining the integrity of the airway is a high priority for humans. We require the ability to close our mouth and refuse to let anything be jammed into it.

Jaw movement and breathing

We need to have jaw movement that is flexible, so that we can move to meet the demands of the music in terms of register, dynamic, and tone color. When the mouth opens, the mandible moves down and back. Sometimes, students move as if they have jaws like a shark…. top and bottom both moving. The top teeth are attached to the mandible, which is attached to the skull. We do not want baby shark! (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=McMzoUhhym4)) This movement involves moving the whole head up and away. Many flutists have a mini version of Baby Sharkitis happening when they breathe… the whole head moves up, away from head joint. Isn’t it easier to move the smaller piece (jaw) and leave the bigger piece (skull) alone?

If you simply stop tightening the jaw closing muscles, your jaw opens in cooperation with gravity. If you go into an unbalanced head position on purpose and repeat this activity, you’ll notice that it’s more work to open. [If you don’t remember what I mean by unbalanced head, click here (https://thefluteexaminer.com/pain-in-the-neck/) to read “Pain in the Neck” from June 28, 2018 to find out more about head balance.] So what? When you head is off balance, you’re working harder to open your mouth. This pattern is also impacting your hyoid bone, which is then influencing the quality and ease of your tongue movement.

Once we understand where the jaw moves from and discover where the muscles are that do this work, we can make better choices about what we’re doing here. Ultimately the choices are related to our resonance, breath control, tone color, and articulation.

Lots of great information -presented clearly and simply. Thank you!