Previous articles in this series discussed where the air actually goes—mouth, nose, trachea, and lungs—and contained information about the ribs, diaphragm, musculature that acts on the ribs, and the abdominal cylinder. The focus of this article is the musculature of the pelvic floor. For each of these articles, I’m going to restate the main idea, which is that there are lots of moving parts associated with breathing, and any time any of those parts is not able to move in the right direction, at the right time, and/or with the right amount of ease and freedom, it’s going to impact the quality of our breathing.

Disclaimer: Many people are uncomfortable discussing the pelvic floor muscles and I recommend skipping this muscle group with middle school and high school students. My college students are not very interested in learning about this muscle group and are generally pretty uncomfortable. I will make this as painless as possible.

Where are these muscles?

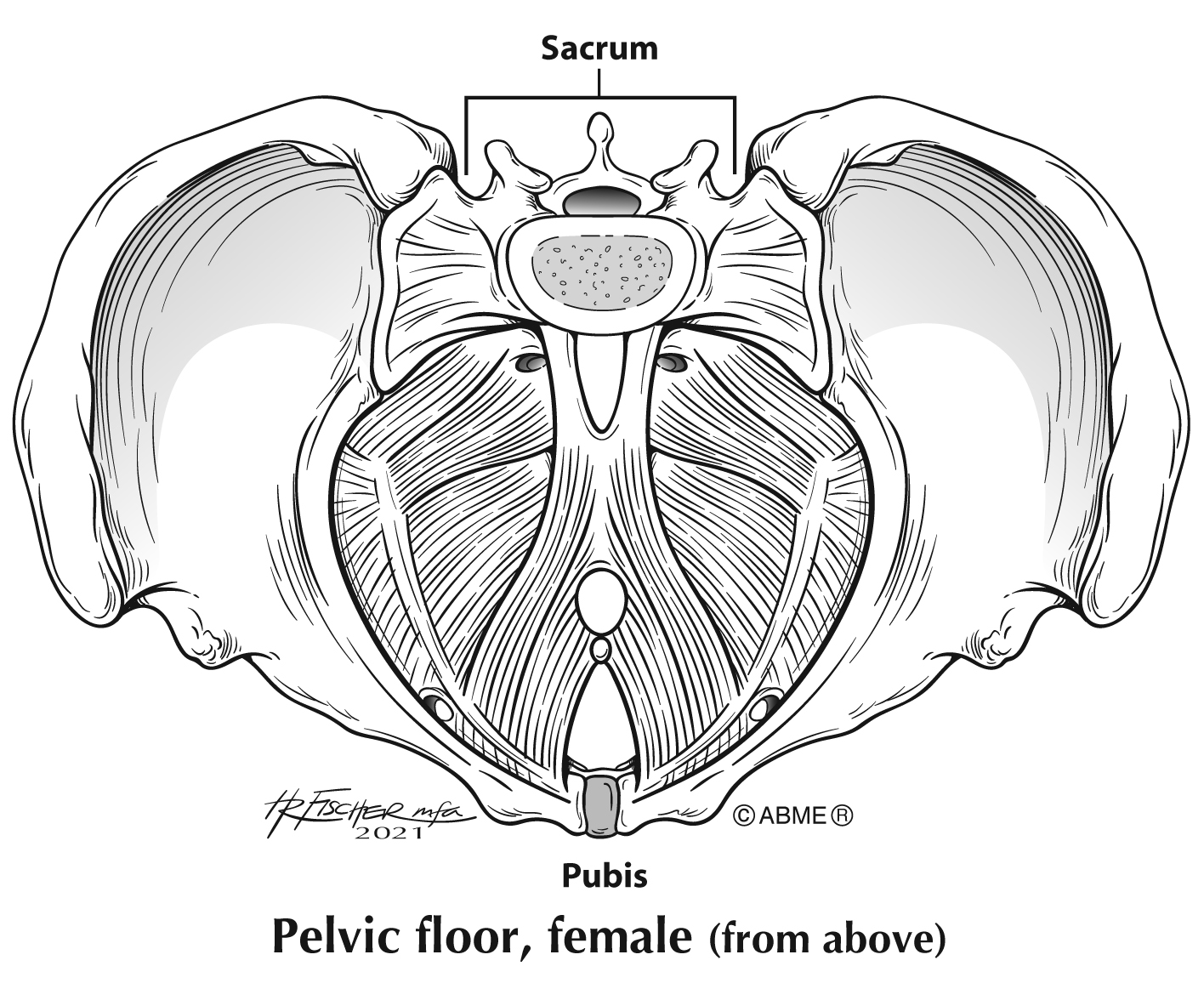

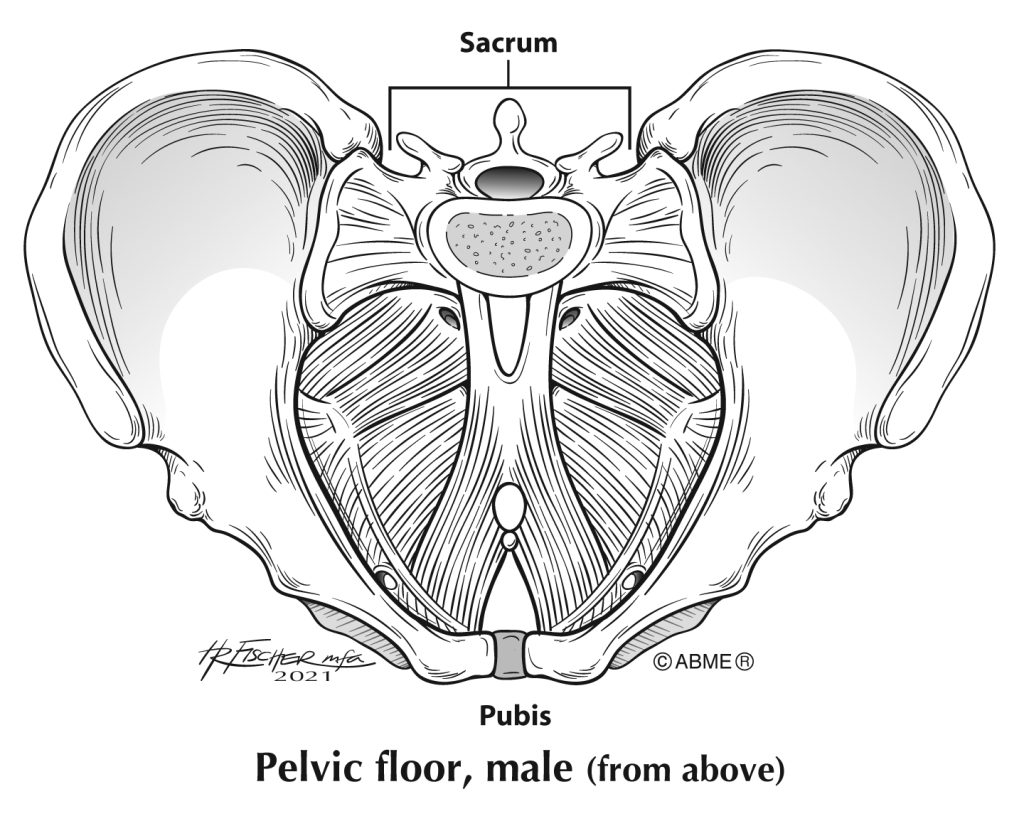

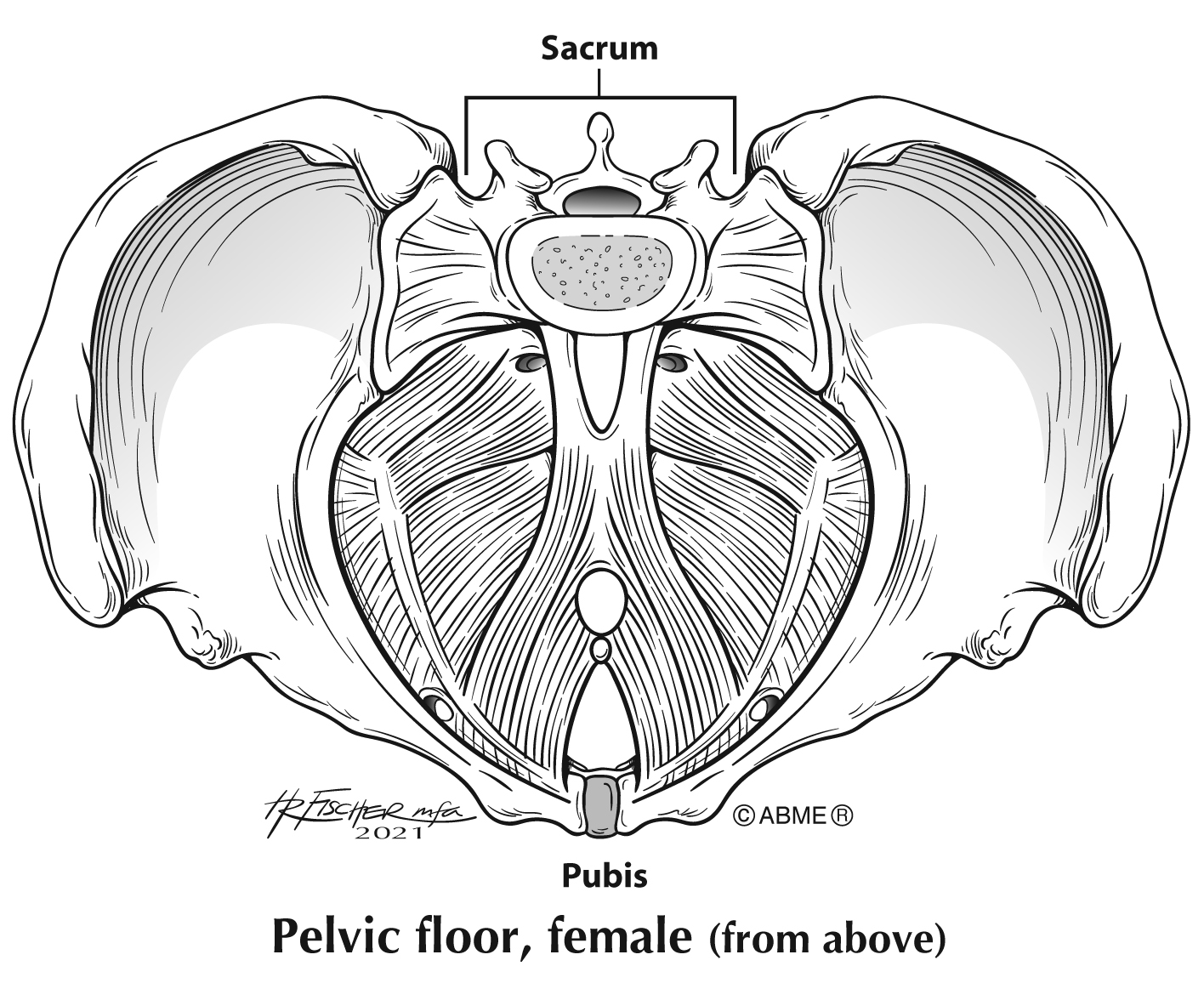

The muscles of the pelvic floor run from side to side between the ischial tuberosities (rocker bones) and between from front to back between the pubis and sacrum. They are the muscular bottom of the bony pelvis; hence the name, pelvic floor.

Kegel exercises are designed to engage the muscles of the pelvic floor. Another way to find the muscles of your pelvic floor is to think about what you would have to activate to stop urinating midstream. Women can have problems with pelvic floor musculature postpartum or with pelvic organ prolapse. Men can also have problems these muscles. There are physical therapists who specialize in treating the pelvic floor musculature.

What should the muscle of the pelvic floor be doing?

As the diaphragm descends when we inhale, it puts pressure on all of the viscera between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor. The abdominal cylinder expands outwards and the pelvic floor descends. A simpler explanation is “the diaphragm contracts and the pressure causes the stuff inside to move down and out.” The pelvic floor should be able to descend in response to the pressure. When we exhale, the muscles of the pelvic floor release, because they do not have to deal with the pressure coming from above. They spring back to neutral when the pressure releases. These muscles ideally should move responsively with the breath. Their movement should not feel like work. Pelvic floor and diaphragm should be moving in the same direction: down during inhalation and up during exhalation.

How do we mess this up?

If the muscles of the pelvic floor are in a chronically tightened position, then they cannot respond to the downward pressure of the viscera. This means that the diaphragm cannot fully contract because there’s not enough room for the stuff inside. This is the same thing that happens when muscles of the abdominal cylinder are chronically tightened. If they cannot allow for movement outward, the diaphragm’s movement is also limited.

What causes chronically tight pelvic floor muscles?

Many things can contribute, including chronic stress, holding in urine or gas, sitting too much, positioning of the pelvis, and/or tightness is other surrounding muscles group. It’s beyond the scope of this article to explain all of this. It’s complicated.

Something easy that can help!

Try squatting down and taking a breath. Ideally, your heels will be on the ground. If you have trouble getting into this position, roll up a towel or a yoga mat and stick it under your heels and try again. Hopefully, you will find that it’s very easy to get a great breath in this position. Play some stuff on your flute. I do this experiment in my college classes and it’s amazing for wind players and singers. They have huge smiles and say “I sound amazing right now. I feel ridiculous but the sound and resonance is killer.” Yes, it’s not magic. There’s a reason. While squatting, the muscles of the pelvic floor are not tightened. This is why it’s the default position for natural childbirth and bathrooming. I think I must have spent a year squatting down, sounding great, standing up and not finding the same sound. Going back to squatting, standing up, repeat….. Eventually, I was able to find the right coordination to allow the breathing parts to move together appropriately.

Bonus fun fact!

One of external hip rotators, obdurator internus, interdigitates with the muscles of the pelvic floor. Translation – what you’re doing with your hip joints is affecting your pelvic floor and vice versa. Here’s another whole body connection to add to our list. It’s all connected, folks.