Previous articles in this series discussed where the air actually goes—mouth, nose, trachea, and lungs—and contained information about the ribs, diaphragm and musculature that acts on the ribs. The focus of this article is the muscles of the abdominal cylinder. For each of these articles, I’m going to restate the main idea, which is that there are lots of moving parts associated with breathing, and any time any of those parts is not able to move in the right direction, at the right time, and/or with the right amount of ease and freedom, it’s going to impact the quality of our breathing.

Cylinder or Wall?

Often, we see references to the “abdominal wall,” and I would like you to replace that with “abdominal cylinder.” A wall is a flat, immoveable structure with only two sides, a front and back. A cylinder is a 3D shape and, in the case of the abdominal cylinder, it can move in all directions.

Abdominal musculature

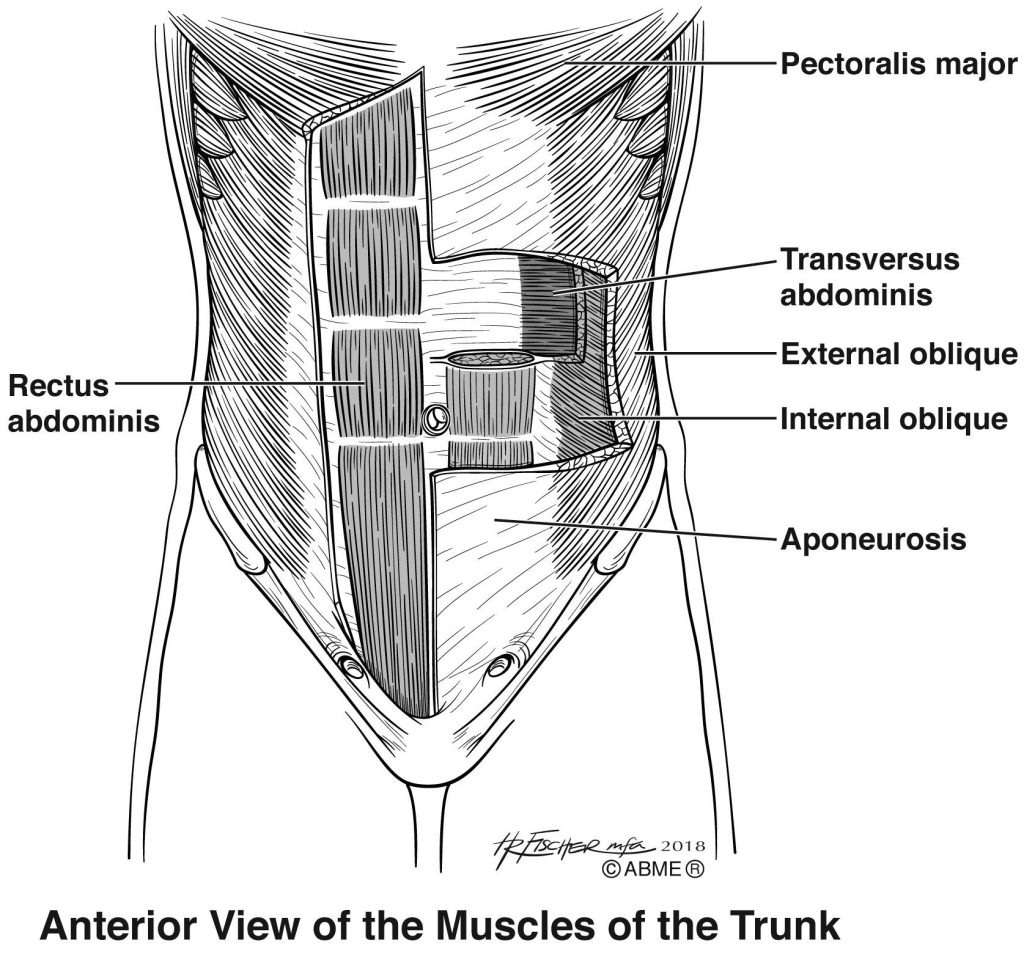

There are 4 sets of abdominal muscles and they all connect various parts of the pelvis to the sternum and/or ribs. These are paired structures, meaning that you have one on the right and one on the left. It’s not necessary to know the exact attachments, but this information is listed below for those of you who want it.They appear in layers and we’ll go from the outside in.

The rectus abdominus is the outermost layer and it connects the pubic symphysis and pubic crest with the cartilage of Ribs 5-7 and the xiphoid process of the sternum. On bodybuilders, these the RA muscles are the ones that form the “six pack.” It’s job is to flex the spine and tilt the pelvis posteriorly.

Underneath the rectus abdominus is the external oblique. It runs from the external surfaces of Ribs 5-12 to the front part of the iliac crest of the pelvis and the abdominal aponeuosis (a line of connective tissue in the center). Working together, both external obliques flex the spine. If just one external oblique is working, it flexes the spine to the same side and rotates the vertebrae to the opposite site. If you imagine putting your hands into external pockets of your jeans or coat, the way your fingers are pointing (down and on an angle) is the direction of the muscle fibers.

As we keep moving deeper into the body, we find the internal oblique. It runs from the inside surfaces of Ribs 10-12 and the abdominal aponeurosis to the iliac crest of the pelvis and thoracolumbar fascia in the back. Working together, the internal obliques flex the spine. Working alone, the internal obliques flex the spine to the same side. So far, the functions of internal and external obliques are exactly the same. But, when we consider rotation, the internal oblique rotates to the same side. So, if you rotate your torso to your right, you are using your right internal oblique and your left external oblique to accomplish that motion.

The deepest muscle is the transversus abdominus. It runs from the internal surfaces of Ribs 7-12, the iliac crest of the pelvis and the thoracolumbar fascia, to the abdominal aponeurosis. It’s job is to compress abdominal contents.

Which breathing team are they on – inhalation or exhalation?

The correct answer to the question is both. Let me explain. When we exhale, the abdominal musculature is helping to bring the ribs back down and in. They are definitely actively contracting on exhalation.

When we inhale, the abdominal muscles need to be able to lengthen to allow the diaphragm to fully do its thing, which is to contract down. When the diaphragm contracts down, it is also pushing down on the contents of the abdomen (liver, kidneys, intestines, etc) and the abdominal muscles need to be able to release so that these organs and tissues have a place to go. This expansion happens all the way around, not just in front, hence the idea of an abdominal cylinder, as opposed to a wall.

How do we mess this up?

We squeeze with the abdominal muscles all time. This is a problem because they need to release before you can start the next inhalation. If they don’t release, then the diaphragm cannot move fully down and the ribs cannot move fully up and out. Remember the main idea: when any part can’t move in the right direction, at the right time and with the right amount of ease, the quality of the breathing will be impacted. If we think that abs are the only players on the exhalation team and forget about the other muscles that help bring ribs down and in, the movement of diaphragm back up to its domed position, and the recoil of the lung tissue itself, we can end up working much too hard.

Bonus fun fact

In the image above, have a look at the 3 arrow shaped groups of fibers up at the top on each side, under the pectoralis major label. These fibers are the serratus anterior muscles, one on each side, and it blends fibers with the external oblique. The serratus anterior is an important stabilizer of the shoulder blade and this means that what you’re doing with your external obliques is impacting your arm use!