Organization… is relative.

After spending days thinking about how to guide my students to be “organized,” I concluded the issues were not my students. It was my teaching!

I once had a wonderful therapist. She gave me great advice: When you are angry with someone, before acting against them, reframe the situation. Try the negative feeling on for size. For example, if I felt my colleague never listened to me, I might tell myself “He never listens to me while I talk.” To try it on, I would tell myself “I never listen to him while he talks.” Though this is not always needed or effective, it does open a new perspective.

How to organize your students? Try organizing yourself, first!

Below are three ideas to promote a healthy relationship between your student and their instrument.

1. Keep detailed notes on your students, especially during the first lesson.

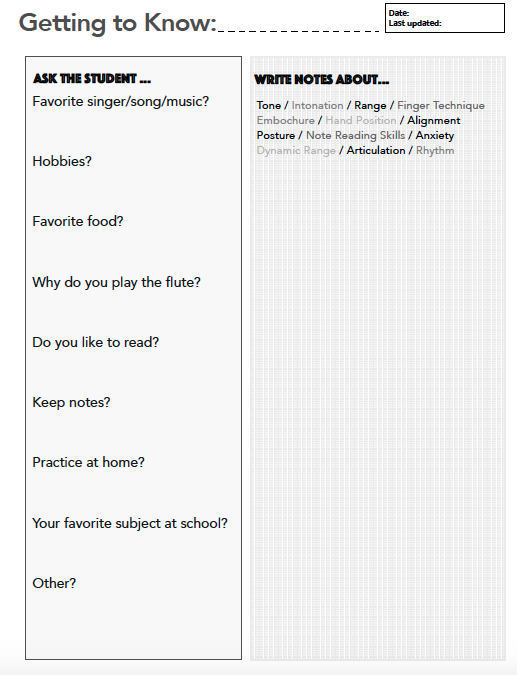

Ask your students questions about themselves and their goals: what do they listen to in their leisure time? Why they play the flute, etc. Most importantly, use a “getting to you know” document that you update over the course of the first few lessons. Observe their playing; How is their posture… lip position, sound, tonguing, and so on. This is especially helpful for students that have started playing flute in a band program or who are coming from a different lesson teacher. If it is a brand-new student, you want to find out about their personality, habits, and general posture before they play.

A checklist could also serve in place of a “getting to know you” document, as long as it covers all bases that are important to you.

Here is my “Getting to know you” Checklist. Click to download.

2. One size does not fit all.

I love being organized… but not all people work the way I do. After spending some time teaching in public schools, I’ve learned that the art of differentiation is key to student growth. As a teacher, you need to find out how your students “tick.” If you have an absolute beginner, ask them about something they love to do. If they are really young, try to observe the student’s strengths and play to them.

Regardless of how they learn, find a way to promote synergy between you and the student.

For example, if you have a student who is often overwhelmed, try not to “over-diagnose” any issues in their playing. “Ah, I see your headjoint is too rolled in…. We need to fix that!” Though it is temping to layout a detailed, step by step plan of how you will fix their playing, …don’t.

Guide your learner in small steps without sharing too much at the beginning.

Set small, achievable goals during the first few lessons that lead to a larger goal. Once you have completed “the” large goal, share with the student the process that got them there. As a teacher, I find these tasks the most difficult. I always want to use my words to explain. I have to remember to model more and say less.

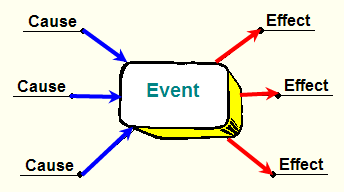

Another way to differentiate is to find out how your students learn. For older students, this can be especially helpful. I’ll never forget the time I took a learning type quiz and found that I’m a visual/kinesthetic learner. It has truly changed my life! Since I’m a visual learner, I like using Thinking Maps to clarify my goals. If you have visual learners in your studio, I recommend framing large goals in a thinking map (see the multi-flow map).

3. Stress the importance of “Deep Work” with your students.

I recently read Carl Newport’s book “Deep Work.” It relays the importance of large chunks of time to do uninterrupted work. Musicians, in general, need long spans of time working on a single task–practice. Modern technologies are often at odds with practice time.

I recently read Carl Newport’s book “Deep Work.” It relays the importance of large chunks of time to do uninterrupted work. Musicians, in general, need long spans of time working on a single task–practice. Modern technologies are often at odds with practice time.

Technology enables us to be distracted at any point. We are just an unlocked screen away from the world. Every time you change tasks (i.e. check your email, social media, etc.) it takes you roughly 23 minutes to immerse yourself in the original task. Though everyone is different, and some may take less time to get back in “the zone,” every minute wasted from your practice session could cost you several down the road. Why? Habit. If we allow ourselves to be distracted throughout the day, our minds will never work at full capacity unless we are aware. There is evidence that people who continually work on “deep work” habits (blocking out chunks of time, refraining from social media, putting phone on airplane while working on an important task), have more time for other projects, are less stressed out, and accomplish more done in less time.

How do we relay this to our students? Enforce a no cell phone policy. If they have it in lesson, it is to be turned on airplane mode or silent (unless their is a possible emergency situation, of course). Demand your students turn their phone on airplane also while they practice. If the student is too young to own a cell phone, make sure the parents understand they have to implement good practice habits from the very beginning: No electronics around while practice takes place; In order to create, we need stillness.

Ultimately you want your students to develop a love for practicing–not organization. Practicing can teach you patience, mindfulness, and diligence–skills that are in short supply in today’s world.

Do you have organization tips? Please share them below.