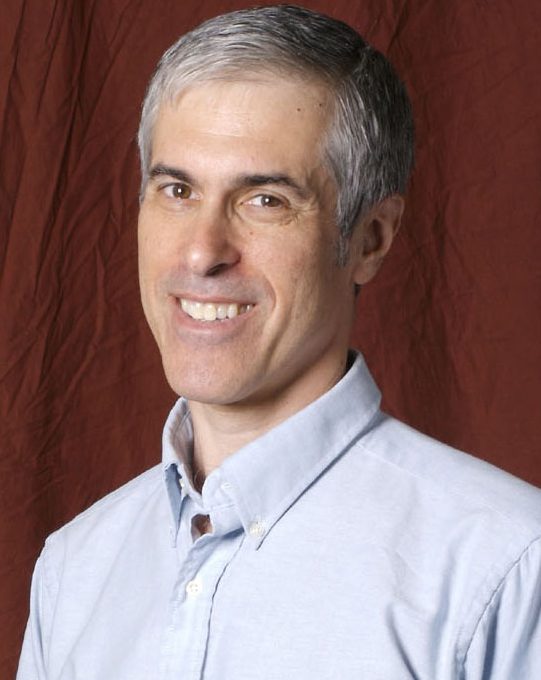

Daniel Dorff has a whole wardrobe of hats, and he wears them all well. He’s a composer, a performer, an editor and a champion of publications, and I recently had the honor of sitting down with him for a conversation about his life and career. It was a free range thing, and in this month’s interview we present the conversation to you, and it really is that—less an interview and more a conversation.

JD: How did you come to a life in music?

DD: There are several ingredients involved in that. Growing up, I wasn’t from a home with musicians in it even though my parents listened to classical music on the radio. But I’m very fortunate to have parents who encouraged me to follow my curiosity, interests, and passions. I started playing recorder when I was eight, like a lot of kids back then, who started with recorder in elementary school. And once I started, it was weird – I could sort of read music the first time it was put in front of me, and I don’t know why. It was intuitive, and I just played all the time and became voracious about sight-reading things with my recorder.

JD: I love that.

DD: I was just a little boy having fun. Then in fourth grade we could learn instruments in school. I wanted to play violin, and my mom (not a musician) thought, “Oh, the sound of somebody starting violin…” She said, “Why don’t you take something like saxophone?”

So I learned saxophone and stuck with it. I mainly was a saxophonist until well into high school. But I got interested in chords, theory, and keyboard a little bit so I could play Beatles and Rolling Stones songs at the piano. I was born in 1956, so when I was eight and starting to learn recorder, that was 1964 when the Beatles first came to the United States. And so I wouldn’t say I grew up with them, but my growth was while they were going through their spectacular and exploratory growth. Popular music of the 1960s was so fascinating for my young and curious ears.

I’ve always had this enthusiasm, and I tend to be intense and curious. As I got older, my interest in music went in several different directions, like figuring out chords to songs. All the music theory I learned came from a Beatles’ fake book with chord symbols which weren’t always right, so I marked up the mistakes in songbooks starting when I was 8. I used to get sent to the principal’s office in first grade for correcting the teacher’s grammar, establishing a recurring motif that later came in handy.

It was amazing that I later wound up in a place (Philadelphia) where a big music publisher (Presser) was looking for a proofreader, and later an editor, because I never even thought about that as a career, but what a great match. It turned what could be a distracting obsession into a win-win in many ways.

In 10th grade, I got interested in classical music and began playing clarinet to be in the school orchestra. My parents let me go to Red Fox Music Camp that summer, and I learned pretty quickly that I don’t have the attitude or commitment to be a professional performer. I had the interest and maybe the talent, but I think I only had abstract talent, without patience or physical talent. Everyone else at Red Fox really wanted to play 6-8 hours a day, and they didn’t get bored because they were so fascinated with improving their skills, and I wasn’t feeling that. For at least a week, I wasn’t sure what to do with my life. But then I started hearing unfamiliar music, some from the 20th century.

One piece that walloped me was the Fantasy for Trombone and Orchestra by Paul Creston. Once I heard that piece, my life suddenly had meaning and a mission! This lightning strike exposed me to the concept of music that I wanted to write. It felt like both jazz and romanticism, and it got me going viscerally and cognitively.

Red Fox Music Camp was a hitchhike away from Tanglewood. Soon after that Creston epiphany, I heard the BSO play The Rite of Spring in person – that’ll do it if you’re getting started composing.

When I got back to school for 11th grade, I wanted to write my own music to play on saxophone. In 1972, there were difficult pieces in the French Conservatory style, and recital pieces by American composers who seemed inspired by getting into the NYSSMA all-state listings. I liked lots of this repertoire, but I was at a point where I wanted to write my own.

JD: But we all know how many people have written for their own instruments. I’m an early music person a lot of the time. Probably three quarters of the repertoire that’s actually designed for flute from the 17th and 18th centuries was written by people for themselves to play.

DD: And back then, that made a lot of sense. Before Beethoven, composers were mainly functioning to serve performers and functions. Beethoven and Romanticism ushered in a different concept of the composer’s role, which gradually led to an explicit disdain for performers’ needs in some niches of the 20th century.

JD: Yeah, you know, I think you’re right. And I think that for a variety of reasons. I have definitely played some things that I think were written for other composers, where it’s not even that it wasn’t idiomatic for flute. It’s that if you’re writing for an audience or you’re writing for a performer, I think you are seeking to make some kind of an emotional connection with another person. And sometimes I’ll play music that feels more like like a proof.

DD: I agree, sometimes in that niche, music was composed to prove a theory or to demonstrate a composer’s intellectual skills. And so, going to college in the 70s, it went without saying that all composers must adhere to this modernist movement or else not be taken seriously. There have been really interesting articles and studies about it. We picture this as what the 60s and 70s were about because that’s what it was in academia, awards, reviews, and the media. But Copland and Barber were doing quite okay. And so were the less famous composers like Dello Joio and so many others. Look at the Dutilleux Sonatine. Although from what I’ve heard, he didn’t consider that one of his “real” pieces because he wrote it early in his career for the Conservatoire and didn’t compose in that style afterwards.

JD: I would believe that because I’ve played some of his orchestral music too. And it’s nothing like the Sonatine. It is no less of a good piece of music, but you know…

DD: I know what you mean, and this is really important. There’s so much music that I wouldn’t compose, that I love listening to and studying. What I don’t like is the expectation that one must compose like someone else’s aesthetics, because I love Bach and Beethoven and Brahms, too. And I wouldn’t write like them – that’s not where my language comes out. There’s so much modernist and expressionist music that I really enjoy, yet it’s not where my personal voice is.

Most of my teachers and classmates scorned the way I wanted to express myself because it wasn’t in fashion like the “modernism” that was imitating what was new way back in the 1920s. But, I don’t want to get too preachy about it because that attitude was 50 years ago, I enjoy a lot of that music, and it is part of what shaped me. And when I was a grad student at University of Pennsylvania, you know what Crumb, Rochberg, Shapey, Wernick, and the theory professors loved talking about the most? Brahms!

Going back to your first question about choosing a life in music: what led me in that direction was how much I loved what I was doing, which developed into writing music to play myself on saxophone, which in the long run I only did a few times, and then I started writing for other people and organizations.

I never got back to saxophone writing and performing as a main focus, but I did get to play in Milhaud’s La Création du Monde. What a great saxophone part! And I played it with a Sigurd Raschèr mouthpiece, because Milhaud composed it for Sigurd Raschèr to play, and I had studied a bit with Raschèr who required this mouthpiece for his students. The Raschèr mouthpiece is quieter than most others, and that allows the saxophone to replace the viola in the string quintet and balance well, as Milhaud oddly scored the piece.

JD: It blows my mind that you studied with Raschèr.

DD: Me too! The so-called Sigurd Raschèr mouthpiece actually was the original Adolphe Sax mouthpiece, and the manufacturer told Raschèr, “Put your name on it.” In the 1840’s it was designed for ensembles of the time, not yet adapted for jazz or modern wind ensemble.

Getting back to our first question, in high school I also started writing music for my friends to play, because that makes sense, right? And I was very lucky to have a high school teacher (Harold Gilmore) who was also Superintendent of Music for the school district. He had studied with Nadia Boulanger and wrote both classical and production music; he wrote songs for Billie Holliday and scored TV shows and commercials back in the 1940s and ‘50s. Then rheumatoid arthritis prevented him from performing as a violinist, and the cortisone treatment for RA ruined his hearing beyond the point of being able to work in the fast-paced commercial recording world, so he switched over to being an educator.

JD: That’s terrible.

DD: Yes, he kept writing to some extent, but he was a dedicated teacher with tremendous knowledge and experience. I probably take for granted how much he shaped me from the start. I grew up in Roslyn, NY, which is a Long Island suburb of New York City. I could get on the train and go to Lincoln Center and Patelson’s music store, which was another wonderful resource that I took for granted. Mr. Gilmore trained me, counseled me, and he didn’t have style prejudices. He knew that you find yourself and learn how to maximize what truly excites you.

Getting back to your first question again, which seems to lead to everything!

By the time I was in 11th and 12th grade, I knew I had a decision to make. My parents were supportive of me following my dreams, while also wanting me to be fully realistic. They were wise about making my own decision and owning it, and about what now we call “due diligence.” So they let me go to Aspen for the summer after 11th grade to really learn about immersion in that world before committing my life to composing; that was probably the most thoroughly galvanizing and ear-opening few months I’ve ever had, except perhaps when I went to Aspen again the following summer.

At the same time, Mr. Gilmore was also counseling 5 of us in the high school who were seriously considering a music career. He told us, “Don’t go into music as a livelihood. Your passion isn’t related to the future ability to raise a family the way that you were raised.”

Two of us said, “I’m going full-steam into music anyway.” The other three took his advice, and a few years later I said, “That was pretty harsh. Why did you say that to everybody?”

Mr. Gilmore answered, “I think you know. If I could talk the others out of a music career just by chatting with them, what do you think would happen when they can’t find work, and then rethink what they want to do with their college education after they’ve already got their specialized music degree? You went into music wholeheartedly because you have the determination it takes. You have the unswayable commitment and are more likely to weather the storm.”

From there I went to Bennington College because I found a CRI record that had music by Bennington composers. There were 4 composers on the faculty of a teeny school. There was no regular performance faculty, but a whole bunch of New York City freelancers took the Vermont Transit bus up on Tuesdays, stayed overnight, and went home Thursday evening. Sue Ann Kahn was the flute teacher there when she was young.

JD: Oh, wow.

DD: Yes, so I knew her when she was around 30 when I was a freshman in college. And Henry Brant was one of the composers on faculty.

JD: I’ve heard of him.

DD: Henry was a flutist first, and then he became a Hollywood composer. He composed Angels and Devils in 1931 when he was 18, scored for solo flute and flute ensemble, and it was the first piece ever composed for flute orchestra. 18-year-old Henry conducted the 20-minute piece’s premiere in NYC, with Barrère as soloist.

JD: I think I’ve played that.

DD: Brant was a wildly imaginative modernist, and also a great teacher of what’s practical. Because he broke in as a Hollywood composer, where time is money in recording sessions, he was emphatic about everybody preparing their music well for the performers’ use. I already was fixated on that, and I still don’t understand why other composers don’t make exquisite page turns and cues. I wasn’t doing it just to be nice to everybody, I was doing it to facilitate performers doing their best in playing the music that I wrote.

I only went to Bennington for one year. It was all about experimenting outside the box, and I wanted to learn music history and craft as well. I didn’t appreciate the unharnessed freedom then. I did want to go back later in life, but to first get a basic education, that’s not where to start. So I did a 180 and transferred to Cornell University. My main composition teacher there (Robert Palmer) loved my music so much that he couldn’t be critical; he wrote the same kind of music as me and was too delighted to find somebody like him aesthetically. He only wanted to pat me on head all the time, so I didn’t learn from him. The other Cornell professor was Karel Husa, who didn’t take me seriously. However, I learned a lot from being around his music and watching him. I love his music, and I loved seeing the unique and visceral way that people react to his personalized atonal expressionism, which really moves people.

This led me to ask myself “why is Husa’s music so different from Penderecki’s? What makes it so visceral? What does he do that keeps the attention of listeners who don’t like modernism?” Eventually I realized Husa’s motive structures are so tight that people don’t even realize it’s far out because it’s easy to follow. Well, that’s a great lesson for any composer. He never said this to me, but from just being around him and playing his concert band pieces, I picked it up.

At Cornell, I got what I was hoping for – I learned terrifically about music history and the real inner workings of structure. For example, Neil Zaslaw, a flutist who became a musicologist, thoroughly researched and taught from source material. Talking about Mozart he told us, “Well, I went to Salzburg and I looked at the royal payrolls and the paintings of the orchestra from Mozart’s years there, to see how many string players were doubling on the performance of this piece.” I love this way of thinking, it’s forensic musicology and actual study of factual history, not just opinions and folklore. And that had a great effect on what I bring to editing at Presser, as well as developing critical thinking in general.

My other music history professor was Don Randel, who later left Cornell and rewrote the Harvard Dictionary of Music. Randel also was a forensic musicologist who had “X-ray vision” into what’s behind the music. I learned more about composing, and about the structural differences between Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert from Randel, than from my composition and analysis teachers.

JD: It’s the thing that lights the spark.

DD: Definitely! I have this insatiable thirst for knowledge that just can’t be quenched. At 68, I feel and think and yearn the same way as at 18. I’m not ready to be old yet, because there’s so much more to discover. Not to radically jump into different worlds of composition, but there are always new sparks to keep the next piece sounding different from the previous ones.

JD: How do you keep it fresh?

I think by being thirsty for new stimulus and keeping my ears open. I don’t ever want to write a piece that’s a fast knock-off of a previous one, and sometimes I turn down commissions for instrumentations that I’ve written a lot for already. So that’s why Trees has narration worked into “a piece for solo flute,” and why Songs of the Open Road has Whitman epigrams for each movement interwoven into a suite for solo flute.

With the various things I do, between my Presser job, promoting my own compositions, and everything else, there are often stretches of time where I can’t focus on composing regularly. But at a subconscious level that I’m not aware of, it seems like composing is going on behind some closed door of awareness, because usually I write quickly after these intermissions away from the piano.

JD: Oh yeah, like your imagination and your brain synthesized it while you were doing something else.

DD: Right. Sometimes people ask me if I have a routine, and when do I write; I don’t understand how anybody can have such a routine, even though some great composers did. If you’re writing music like Tchaikovsky, impassioned and obsessive, to me that is the greatest anomaly, because he was very regimented and he’d be in the middle of a climactic part of the piece, then say, “Oh, 12 o ‘clock! Time for my tea and a walk.” But that’s him, and it’s mentioned in his published diaries. There are times that I’m able to have nights and weekends free and undistracted to get into that zone, and sometimes not. Over the past few months I’ve been writing a 12-movement suite for bass clarinet duo. I’m halfway through it, and most of what’s on paper was composed during the week between Christmas and New Years when I was simply at home and unscheduled.

JD: Sometimes the single most exciting thing I ever feel is that I could live to be 200 years old and I would never be able in all that time to play all the flute music there is in the world that I want to play, both things that haven’t been written yet and things that have. There’s just no way. And I love what you say about continuing to be curious and continuing to grow. Because I think we all ought to be that way.

DD: I think flute players have this appetite more than other musicians. And one of the reasons why I love writing for flute is writing for flute players who want music that was written specifically for them, or that they haven’t played yet. As long as it’s playable, there’s more excitement than resistance to having to learn a new piece or have a new experience.

JD: Yeah. It’s not like string players and flute has more repertoire than most of the other winds, not so much from the 19th century. But… so funny because at Vanderbilt, my office is next door to a violin studio and that professor loves the Sibelius Violin Concerto. I know this because at least one student is playing it every semester and I love it too. It’s really fun, but I always think, “That’s not the only one. It’s not all that there is. Throw a little something else in there.”

DD: So perhaps ask if they know William Schuman’s Violin Concerto. There are a few recordings out there, and it’s published nicely with a piano reduction. I heard that piece when I was in high school. It was one of my “desert island” pieces when I was first learning. It’s jazz influenced, not like Gershwin, but like really serious composers who use polychords like a jazz ensemble. Schuman would mean learning something unfamiliar, and I think audiences can like it because it’s similar to Bernstein. And there are many powerful violin concertos from the past 50 years as well!

JD: Tell me more about working at Presser.

My dad was a lawyer, and his dad was a lawyer. I share that way of thinking, like an old-fashioned counselor-at-law, listening to different claims to figure out what the real truth is. Today that’s more like a judge or a detective. That critical thinking is good for looking at Ives manuscripts and trying to figure out what he “really” meant, when the real answer was he meant different things on different days, and there’s no right answer.

I saw the hours that my dad kept, and that he was burned out and didn’t inherently love his work with a passion, and I thought, “I don’t want to do that when I grow up. I want to do something I really love.” At that age, I hadn’t heard the old saw that if you find something you really love to do you’ll never work a day in your life. That’s a little askew from reality, but it’s still an important concept.

I come home from my publishing job just the way that people come home from university jobs, sometimes worn out and not feeling like doing anything else that evening, but I really love what I’m doing. I sometimes wonder, “if I win or inherit millions of dollars, would I keep working there?” The question is moot (!) but I wouldn’t quit on Day 1, because there’s a lot of what I do and learn creatively that’s stimulated by publishing music by other composers.

JD: I’m so impressed with Presser and always have been. It’s the way it looks, the ease of using those pieces of music compared to what else is available on the market. I honestly, before I started researching you to do this, I was thinking of you as a composer only. I didn’t realize you worked at Presser. And so I am so impressed because it’s my favorite. It’s all the new music, all the American music that you publish. I think probably my first Presser score was the Liebermann Sonata for my junior recital. And I loved everything from the way it looked down to the thickness of the paper and the way it feels. It was wonderful.

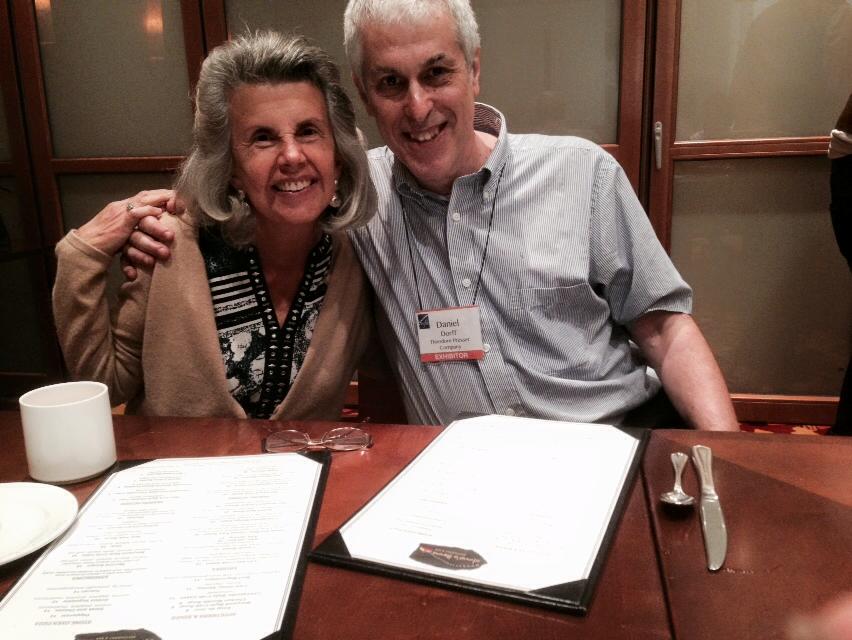

DD: Thank you! I’m very lucky to have worked there for over 40 years under different ownerships and leaderships who’ve kept a commitment to that quality value. The owners are very proud of the things you’re talking about, and I have the green light to invest time in quality control – the owners know that’s what makes us different from most other companies.

Would you like some stories? The Liebermann Sonata came in to us when we had published only a few of Lowell’s pieces. He sent me a cassette tape of Paula Robison’s premiere at Spoleto, I listened to the cassette, and said to some of the other people in the office, “I think this is going to go over well with flute players.” That also happened with Schocker’s Regrets and Resolutions, but over 40 years I’ve been wrong more than right.

Working with composers on new publications, I start by studying the submitted score. Whether it’s handwritten or in any notation software, there are always errors, oversights, and ambiguities. It’s easy for composers to overlook dynamics, articulation, even accidentals, when they’ve heard strong performances already. All composers have different notation habits, and one of the joys of my job has been working with Muczynski, Coleman, Chen, Ran, Harberg, Hoover, Robison, Hailstork, Ewazen, and countless others to figure out how to best indicate what they mean in ways that will be obvious to anyone not already familiar with the piece.

When the first Baxtresser book came to us from Jeanne, it was just a lot of loose leaf sheets with brief comments, and I honestly didn’t think it was going to be a great seller. I told our CEO, “I see an awful lot of work for excerpts that mostly are already in the books from International, or protected by other publishers’ copyrights. Even though Jeannie is great in every way, we have to be so much better than all the other books available, and that’s a lot of work time.” And the CEO said, “Okay, well, we’re taking it, so make it that much better!”

Everyone believed in the book’s potential, and that Jeanne and I collaborating together, could develop it far beyond the working draft. She had concise blurbs about each excerpt, and I felt that Jeanne Baxtresser had a whole lot more to say about every one of them. So we had about 1000 phone calls (early 1990’s before email), and I’d ask, “Let’s say I come for a lesson while preparing for an orchestra audition or concert, and I bring in this excerpt. What do you usually have to coach people about that might get overlooked, like where to breathe, or dynamics, or tonguing?” And Jeanne sometimes answered, “Oh, well, I don’t know that anybody cares what I think!” But when nudged, Jeanne would continue, “You know, when it comes to the opening of Faune, you have to play it one way in an audition and another way when you’re on stage because the expectations are different. If you’re playing Midsummer, where you breathe in an audition will be different from where you breathe in the orchestra.” And this delving-in developed for every excerpt and the preface. She said, “Listen to what the other people are doing around you. They need to listen to you, but you need to know what they’re doing, which is why the piano reductions are so important.” And gradually Jeannie and I trained each other how to get the best questions and answers from each other, leading to the thorough “added value” of that book beyond the excerpts themselves.

JD: That book is so iconic! Just recently I had to buy my second copy because the first one just fell apart. I think I bought it in fall 95. I was a sophomore in college.

DD: 1995, it was a brand new book when you got it!

JD: Yeah.

DD: Once maybe around 2000, I was lined up to go into an event at an NFA convention, among a bunch of people outside the door. Tammy Sue Kirk was in that crowd and noticed my name tag, and she was carrying her copy of the flute part from Baxtresser. It was tattered, wrinkled, and stained, and Tammy looked at me and was so embarrassed. She said, “Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t take care of it!” I answered, “Are you kidding? You’re using it the way it’s supposed to be used! I want to take a picture of your book and send it to Jeanne because it means you’re carrying it around everywhere you go.” So that’s why the Parloff excerpt book has that funny look on the cover, showing the excerpts with heavy wear and tear! Well, also I saw a British publisher’s rental catalog that had the the first page of Elgar’s Violin Concerto on the cover, with scribble all over it and a coffee stain, and a note to rental librarians: “Do not return your music like this.”

JD: What are you working on now?

DD: There’s a lot swirling around lately, so I’ll tell you about 2024. In February, Faith Wasson and friends premiered a flute/viola/harp trio called Midsummer Daydream. But actually this was the premiere of the new scoring and new title for a piece composed for Angela Massey’s Astralis Chamber Ensemble during the pandemic. The original commission was for flute, trumpet, and harp, and the original title was Atomic Turquoise (long story). Over time I realized this music was a gentle scherzo with a wedding scene in the middle, needing a new instrumentation and title more in line with what the piece is about.

Oddly enough, right after making that rescoring, I got a flute/viola/harp commission from April Clayton’s trio Hat Trick. April knows a lot of my flute music, the trio’s harpist had enjoyed performing my Serenade for Flute and Harp, and the violist plays a lot of rock and jazz, and likes the way I write for viola because there are some funky solo pieces. So that was a perfect match. The first time we zoomed together to talk about it, David Wallace (the violist), mentioned a possible premiere at the Big Sky Chamber Music Festival in Montana. I immediately lit up and said, “ding, ding, ding, you just gave me a concept for the piece in this first discussion, because I’ve been to Montana and was awed by the big sky, both day and night.” This fits so perfectly with how I think and feel about the world and music and my own experience of being there. In her interview for Flute Talk, Cindy Anne Broz pointed out that my many nature titles come from real experiences, not about places I haven’t been, and this new trio became called Big Sky from the start. Hat Trick premiered it on tour of the Salt Lake City region last fall, then went to Germany and recorded it for a Bridge Records released scheduled for April 2024.

JD: They are so good! I reviewed their first CD for the Flutist Quarterly, and was just so impressed with April, but also with the whole group.

DD: They’re all wonderful players and they play so well together. They flew to Germany because there’s a recording engineer in Bremen who’s the world’s best at recording harp. And Kristi (the harpist) was able to borrow a harp from the Principal Harp of the Berlin Philharmonic.

JD: As you do.

DD: And for what I’m working on now, if I’m allowed to say a word other than flute…

JD: You are!

DD: My biggest excitement, the kind that can even be fearful because it’s so exciting, is that on April 13, I have a new clarinet concerto being premiered by the South Dakota Symphony by their principal player who I used to play in orchestra with ages ago. He’s retiring after 37 seasons this spring, and the orchestra offered him the means to commission a concerto to premiere for his final appearance. This concert will be livestreamed at 7:30pm Central on April 13, via the South Dakota Symphony’s website, so everyone can hear it.

I’m presently writing a 20-minute suite for two bass clarinets, and after that the next piece will be for 2 C Flutes and Piano, commissioned by Laurel Zucker for an upcoming CD.