Humans take around 22,000 breaths each day. Isn’t it a relief that your body does this on its own and that you don’t have to remember to take each of these 22,000 breaths? As flutists, we are always searching for ways to take in more air, to be more efficient in how we use that air, and to be able to take fast breaths when necessary. For all wind instrumentalists and singers, how we use air is different from normal everyday breathing in two ways. First, our breathing as musicians is triggered by intent. We choose when and where to breathe. As regular humans, this is something that our brain takes care of through chemical sensors which monitor the amount of carbon dioxide in our blood. Second, we are modifying the exhalation part of our breathing cycle. The sound is produced with the air coming out, which does require change in how we approach the air going in.

This article is the first of a series that will explain where the air goes and where it does not, the structures of breathing, the musculature involved with the movement, and the choices we make with all of this information. Some of these choices can make us very efficient and other choices can make us work harder than necessary. Here is the main idea I want you to understand about breathing: There are lots of moving parts and anytime that any of those parts is not able to move in the right direction, at the right time, and/or with the right amount of ease and freedom, it’s going to impact the quality of our breathing. Are we going to die? Not likely. Are we going to end up with a breath that doesn’t work as well as we’d like for flute playing? Absolutely.

Where does the air actually go?

This is the easy question and my students usually look at me like I’m crazy when I ask. The answer is mouth or nose, trachea, lungs and then back out along the same path. That’s it… nowhere else.

Mouth and Nose

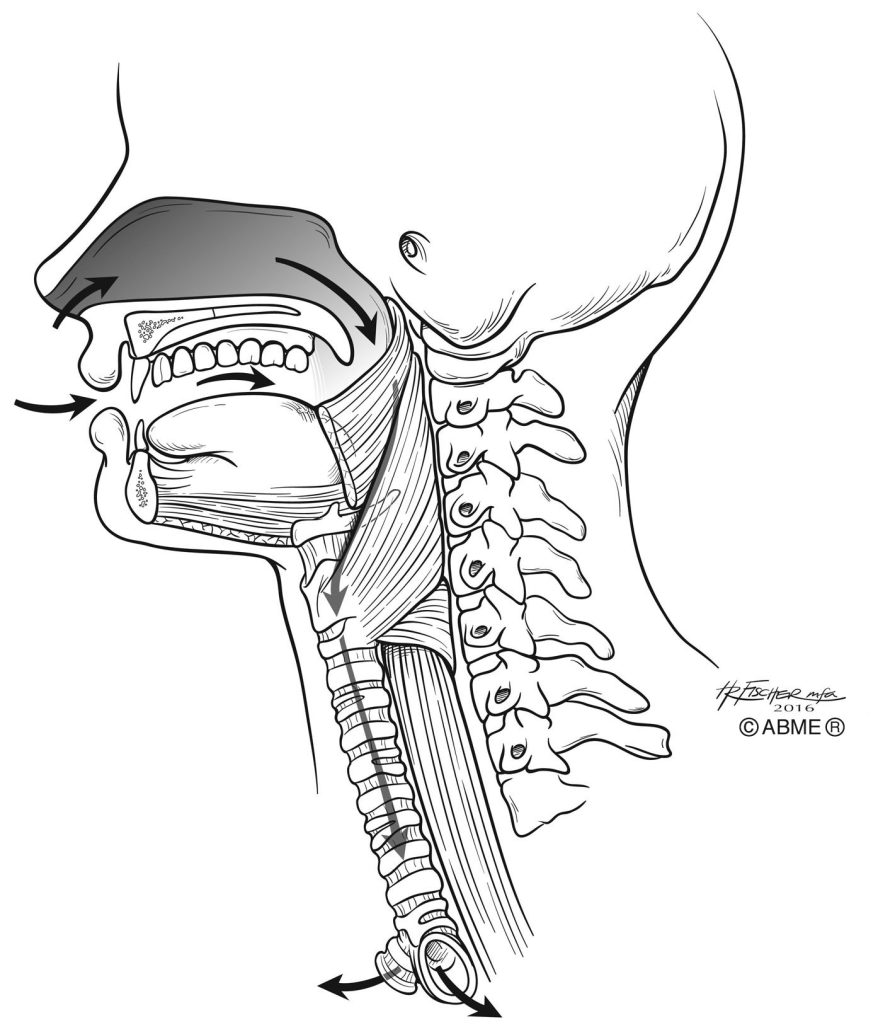

Air goes in through your mouth or through your nose. Both structures are lined with sensors that give feedback about how much air is going through, the temperature of the air, and how fast the air is moving. Looking at the image below, I want to draw your attention to the gray space behind your external nose. Your nasal cavity is in your head, not on your face!

Why are we taught to breathe in through the mouth for wind playing? There is less resistance, the space is bigger and we can get more air in faster. However, there’s lots of research now about how important nasal breathing is for overall health. I highly recommend this fabulous book called “Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art” by James Nestor. The author combines recent research in pulmonology, psychology, biochemistry, and human physiology along with thousands of years of medical texts in an attempt to help us all breathe better.

Here’s a fun experiment. Next time you’re playing your flute, take a couple of breaths in through your nose and see what happens. Do you find that you do something weird with your tongue when you breathe in through your mouth that you do not do when breathing in through your nose? Hmm…. file that away for later.

Trachea

The air continues on its way through the trachea, which is a tube right in the front of your neck. The average trachea is around 4 inches long and a little bit smaller in diameter than a quarter. If you feel around the front of your neck, notice that it feels like a vacuum cleaner tube. There are rings of cartilage that are C-shaped and the open side is towards the back. These rings are holding the trachea open. Air management is a huge priority for our brain as it works to accomplish its primary job, which is “I must protect my human.” The tube the air goes through is open all the time. The other tube in this area, the esophagus, sits behind the trachea and it’s only open when food (or vomit, sorry) is going through.

So, what do teachers mean when they say, “You need to open your throat,” if the trachea is already open? My first thought is that the teacher is hearing some kind of throat noise and that is often coming from trying to use the pharyngeal muscles, which are used to swallow and vomit, to help move the air. These muscles really have nothing to do with air. Food and water need to be swallowed, air just goes. These muscles are labeled in the above image.

Lungs

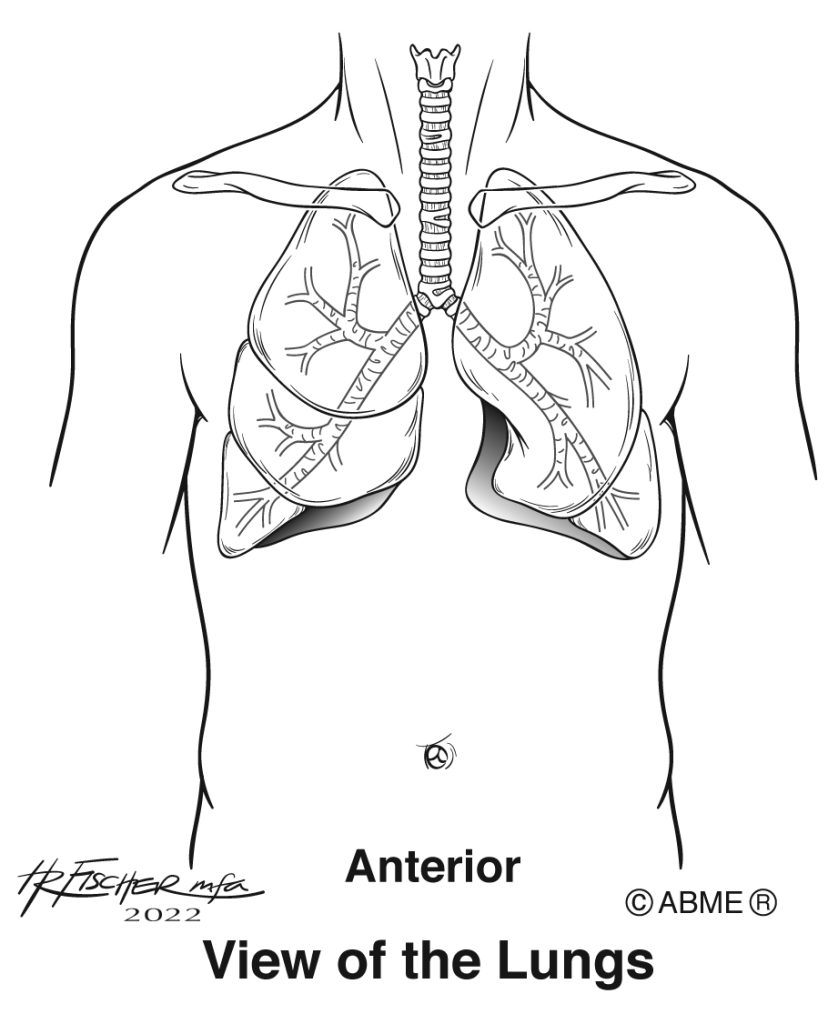

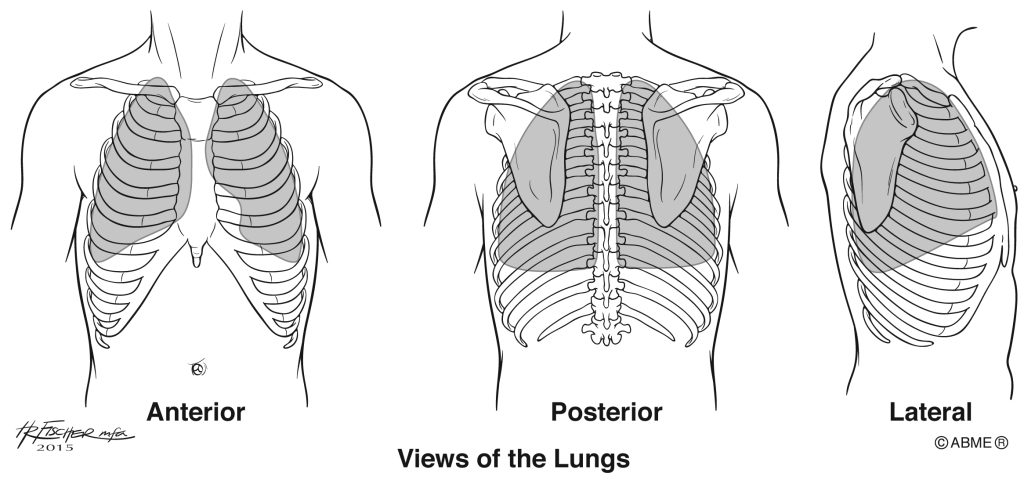

From the trachea, the air branches out into smaller and smaller tubes in our lungs. Have a bit of a think about where your lungs actually are? How big they are? Many people are surprised to find out that they are actually smaller and higher up in the body than they thought. The bottom of the lungs in the front isn’t much lower down than the end of your sternum, but they do go down a bit further in the back. The highest point of the lung is actually right above your collarbone. The gray area represents the location of lung tissue.

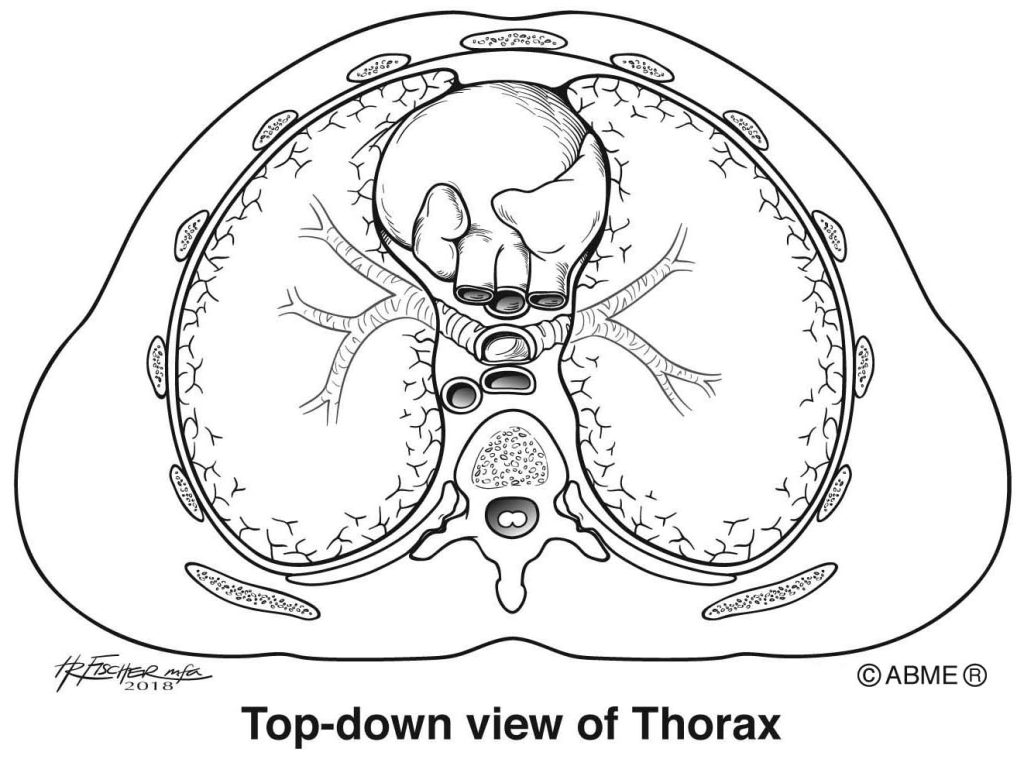

Lungs are not only in the front! They are also on the sides and in the back. The perspective of image below is looking down from above. The front of the person is facing the top. The round thing in the middle is the heart and the blobs on each side are lungs! The lungs fill the thoracic cavity and snuggle right up against the spine. So, if a teacher says “breathe into your back”, that’s correct! Also breathe into your front and your sides!

For purposes of this article, we don’t need to talk about gas exchange and alveoli and all of that. Air comes into the lungs and then it goes back out. There absolutely is movement in the abdomen below the lungs, but it is NOT movement of air. Lungs are not muscles and they cannot move themselves. There are other moving parts that are responsible for getting the air into and out of the lungs, which will be discussed in future articles. The next article will focus on our ribs, which are very important breathing structures.