I just finished reading a fabulous book called “Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art” by James Nestor (https://www.amazon.com/Breath-New-Science-Lost-Art/dp/0735213615). The author combines recent research in pulmonology, psychology, biochemistry, and human physiology along with thousands of years of medical texts in an attempt to help us all breathe better. I’ve been thinking about so many fascinating things that I learned from this book. Then I started watching an online course for manual therapists by Tom Myers, (https://www.anatomytrains.com/about-us/certified-teachers/tom-myers/) the author of “Anatomy Trains,” and he mentioned an interesting fact about the diaphragm that I did not even think about until he pointed it out. Here are some other fun facts about the diaphragm, a vital part of our breathing apparatus, both as humans and as flutists.

1) The diaphragm is a thin sheet of muscle that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity.

2) It is attached to the inside surface of the lower 6 ribs and bottom of sternum, and connects down to the lumbar spine.

3) The diaphragm pulls down on its central tendon, which is attached with connective tissue to surround the lungs.

4) It is dome shaped, while at rest. Think of a big coffee filter upside down. The dome is higher on the right side because the liver is underneath.

5) The diaphragm is not oriented vertically, like a book on your stomach when lying on your back. It’s more horizontally oriented, but also not parallel to the floor—it’s lower in back due to its attachment to the lumbar spine.

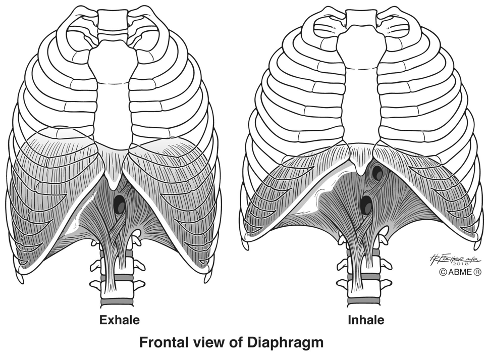

6) When you inhale, the diaphragm contracts down towards the floor. When you exhale, it releases back to its domed position; therefore, it is active on inhalation, not exhalation.

7) We can voluntarily contract our diaphragms by taking a long, slow, deep breath, but the diaphragm also contracts without us telling it to do so. What would our experience be like if we had to consciously attend to every breath we took?

8) The word “diaphragm” is related to the Greek word for mind: the diaphragm muscle is controlled by the phrenic nerve, and its Greek root phrenology designates the mind as well as the muscle. (Chaitow, L. Bradley, D., & Gilbert, C. (2013). Recognizing and Treating Breathing Disorders: A Multidisciplinary Approach. (2nd ed.) Churchill Livingstone.)

9) Your heart literally rides up and down on your diaphragm when breathing because the heart’s pericardium is attached to the diaphragm’s central tendon by ligaments.

10) The diaphragm doesn’t have many sensory receptors, so you don’t feel it moving directly inside your body. What you do feel is the movement of your ribs and abdominal expansion.

11) The air you are breathing is in your lungs, which are above your diaphragm. The movement you feel below your diaphragm, in your abdominal area, is NOT air. This movement is the viscera inside that is being gently pushed out in all directions when the diaphragm contracts downward.

12) The diaphragm also has a postural function. It works together with the abdominal muscles, pelvic floor muscles, and lower back muscles to create dynamic postural stability. In other words, the diaphragm helps the middle of our body find stability so that our limbs (arms and legs) can do their thing effectively and efficiently.

13) In massage therapy school, I learned that you can feel part of the diaphragm from the outside. If you curl your fingers up and inside your ribs right by the bottom of your sternum, you are touching your diaphragm. Each exhalation, you can sneak your fingers a little bit farther in. Warning—this is not comfortable for most people.

14) The diaphragm increases abdominal pressure to help the body get rid of vomit, urine, and feces. It also places pressure on the esophagus to prevent acid reflex.

15) There are three openings in the diaphragm—one each for the esophagus, the aorta (your biggest artery) and the vena cava (your biggest vein).

16) How far does the diaphragm actually move during inhalation? “Normal diaphragmatic excursion should be 3-5 cm, but can be increased in well-conditioned persons to 7-8 cm.” (http://www.scymed.com/en/smnxkk/kkdgbdf1.htm)

17) Hiccups are caused by involuntary spasms of the diaphragm.

18) Click here to see an animation of the diaphragm in action around the time 0:45. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JqFWUjxI1Q

Click here to see another animation which includes movements of the diaphragm.

19) For those students who were told “You must breathe from your diaphragm!” By well-intentioned teacher, Yes!!!!! You can’t not breathe with your diaphragm!!!

20) Finally – the new fact that I learned from Tom Myers – the diaphragm is the only muscle that crosses our body’s midline. Everything else is on one side or the other.

Happy Breathing!

“Yes!!!!! You can’t not breathe with your diaphragm!!!”

Are you saying that the diaphragm is used for exhalation /support? I’m rather confused as to this issue.

The diaphragm contracts downward during inhalation and releases back to its original dome-shaped position during exhalation. Students are often told by teachers that they “need to breathe more from the diaphragm” when they are missing something in relation to breath support. Maybe they are asking for fast air speed, more air volume, or a more consistent air stream. The problem isn’t caused by a diaphragm that’s not working – if you are breathing, then it’s moving.