Previous articles in this series discussed where the air actually goes—mouth, nose, trachea, and lungs—and information about ribs. The focus of this article is the diaphragm. For each of these articles, I’m going to restate the main idea, which is that there are lots of moving parts associated with breathing, and any time that any of those parts is not able to move in the right direction, at the right time, and/or with the right amount of ease and freedom, it’s going to impact the quality of our breathing.

The diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle separating the thoracic and abdominal cavities, is responsible for around 75% of the work of inspiration (inhalation). It is attached to the inside surface of the lower 6 ribs and sternum and the lumbar spine. The diaphragm is not parallel to the floor inside your body, it’s actually lower in the back because of its attachments to the lumbar spine.

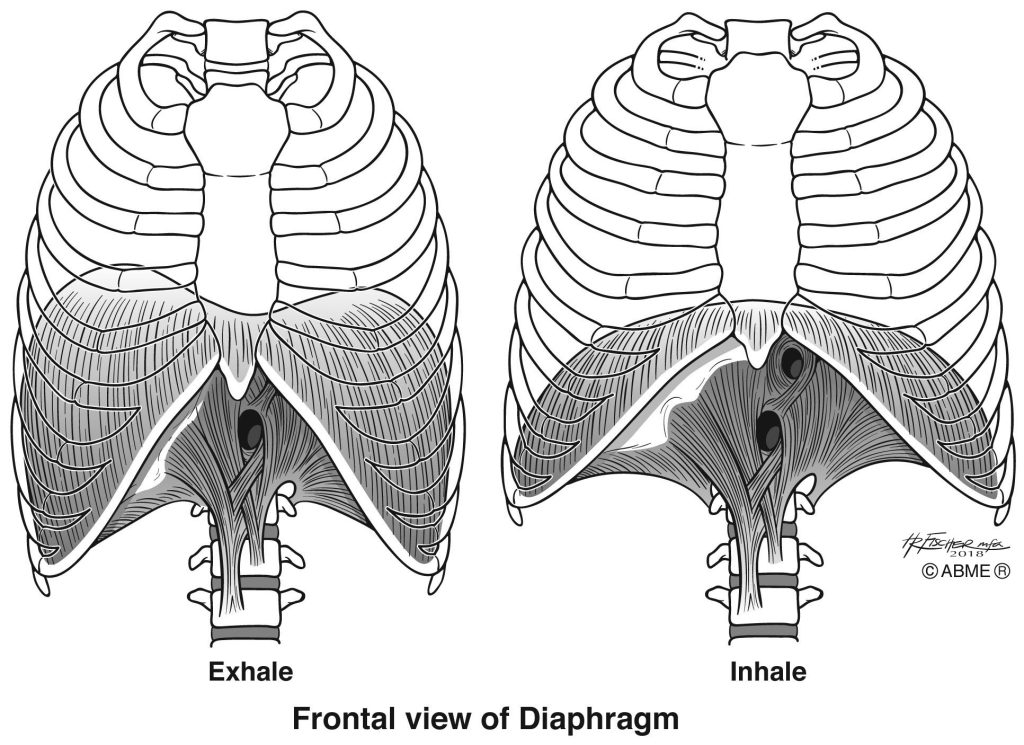

The diaphragm is a domed structure while at rest, think of a giant upside down coffee filter. The dome is a bit higher on the right because the liver is under there. When you inhale, the diaphragm contracts in the direction of fibers and pulls down. When you exhale, the diaphragm releases back to its domed starting position. Therefore, the diaphragm is doing it’s muscular work during inhalation.

How far does the diaphragm actually move during inhalation? “Normal diaphragmatic excursion should be 3-5 cm, but can be increased in well-conditioned persons to 7-8 cm.” (http://www.scymed.com/en/smnxkk/kkdgbdf1.htm)

Your lungs are above your diaphragm. The movement you feel there is the movement of air. There is also movement below your diaphragm, but it’s not air! When the diaphragm contract downs, it pushes the viscera down as well, which creates the movement that you feel.

Going back to the main idea about breathing being a series of coordinated movements: anything that prevents the diaphragm from its maximum excursion down during inhalation or prevents a smooth full release back to its starting position is going to impact your breathing. Future articles will discuss these relationships in more detail but what you’re doing with your pelvis, your abdominal muscles, and the muscles in your pelvic floor influences how your diaphragm moves.

During inhalation, the diaphragm pulls down and the ribs are moved up and out by several different muscle groups. Rib movers will be the focus of the next article in this series.