The Flute Examiner’s collaboration with New York Women Composers Inc., featuring flute works of NYWC members (including free PDF perusal copies) has so far covered twenty-one pieces. This, however, is not the only project concerning the flute that NYWC is involved with. The nonprofit publisher American Composers Alliance (founded in 1937 by Aaron Copland, Marion Bauer, and several other composers in their spheres) shares a number of members, and their music, with NYWC. Enough music, in fact, to begin creating substantial NYWC-themed anthologies.

Flute Music of New York, with nine works for solo flute, is one such newly-released ACA anthology. The book covers half a century (1974-2015), and several of the works make their publishing debut here for the first time. It includes:

Marilyn BLISS – Encounter (1975)

Ann SILSBEE – Three Chants (1977)

Elizabeth R. AUSTIN – Sonata (1991)

Gina GENOVA – For Solo Flute (1993)

Marilyn BLISS – Phantom Breeze (1994)

Sarah MENEELY-KYDER – Air and Water (1996)

Margaret FAIRLIE-KENNEDY – Spirit Man (2003)

Marilyn BLISS – Murali (2004)

Joyce Hope SUSKIND – Celebration (2015)

Several of these works have been newly typeset from manuscripts, or re-engraved to fix errors (notably Elizabeth R. Austin’s Sonata, previously featured on The Flute Examiner – you can find both the new and old scores at that link, for a neat look at edition updating). Another work, Gina Genova’s For Solo Flute, was recovered during the creation of the anthology. Marilyn Bliss’s Murali, featured in several National Flute Association competitions, is this month’s addition to the Flute Examiner’s perusal pages.

Flute Music of New York, in print and as a PDF, can be bought from the American Composers Alliance, and the print edition can also be ordered through your preferred flute retailer.

Below, I touch on each work in the book, beginning nine years before the founding of NYWC.

Marilyn Bliss: Encounter (1975)

It’s quite cool that there are three Marilyn Bliss works to appear in this anthology, as she was a founding member of NYWC. (I also think it also provides an intriguing overview of her consistent stylistic decisions, and evolution, over thirty years.) The early-career Encounter, written when the composer was 21, is the most musically self-aware of the three Bliss pieces in this anthology. Development is driven explicitly by expanding and contracting intervals, with much of the larger structure of the work shaped by the interval choices.

The composer describes her conception of the work:

A sly and slithering creature encounters an adversary while on its daily rounds. It scurries, looks for cover, then camouflages itself. The adversary helps itself to the creature’s motive, violently transforming it in the flute’s high register. The adversary hunts for the creature, unsuccessfully looking for it high and low, eventually exhausting itself with huge registral leaps. Cautiously, the creature emerges from hiding, then stretches itself in the low and middle registers. Reassured, it relaxes, safe for another day.

The opening motive, sly and slithering. Notice that no pitch class changes more than a semitone from its previous in each group.

Midway, the creature’s motive, captured by the adversary, is transformed at climax; slithery chromatics are interrupted with larger intervals, then a return to the opening microtonal theme.

In 1979 Encounter entered the catalog of JP Zālo Publications (a publishing project of flutist James Pellerite, focused on contemporary music for both the Boehm flute and the Native American Flute). In 1993 it was included in the first volume of Zālo’s anthology The Contemporary Solo Flute, and in 1995, two years after the Zālo anthology, Pellerite would commission Bliss for the Native American flute solo Phantom Breeze.

Ann Silsbee: Three Chants (1977)

Ensoleille (bass) • Frissons (c flute) • Refrain (alto)

Ann Loomis Silsbee’s works tend to hold what we, as flutists familiar with Jolivet or Bozza, might refer to as a sense of mysticism. They echo; they swirl and invoke. Explicitly, too. In Runemusic (for solo cello) she assigns twelve musical fragments as her twelve runes to transform; in Letter from a Field Biologist (for two pianos, premiered by herself and Julius Eastman) she describes the swelling and ebbing torrent (very much worth a read) of a monarch butterfly migration.

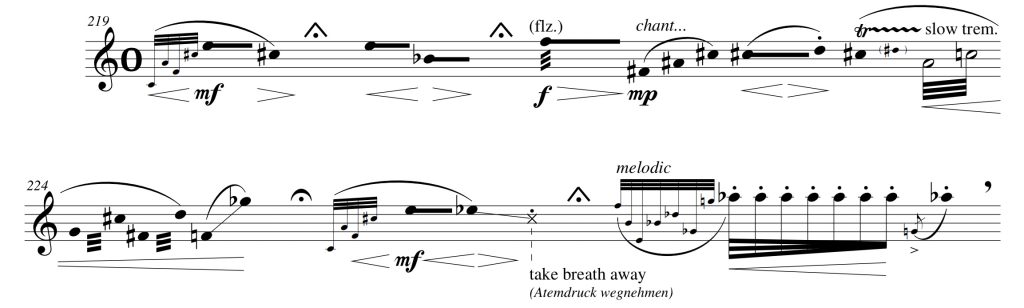

In Three Chants, typeset in 2022, the flute (and optionally, alto flute and bass flute) vibrates and shivers; it sings songs lush and strange. Layered throughout the three movements (also playable on their own, per the composer’s guidelines) are numerous extended techniques. They include singing and playing, multiphonics, quarter tones, tongue attacks, air sounds, and careful reverberation, and the extended techniques are just as developmentally important as motive transformation.

The first movement, Ensoleille opens with two lush timbral trills, beginning on a C# (with a pickup from a low D), supported by the voice. The second theme interjects. A third timbral trill, on C, leads back to C# – this time transformed, a tremolo using the low D.

First movement, second page. Multiphonics are used as tone color to increase tension in restatements of the themes. Here, the second theme’s rhythm is pulled and twisted.

The second movement, aptly named Frisson (“shiver,” “fragment”), uses a variety of textures when repeating notes. Each repetition ends with a dissolution of the note in some form.

One of Silsbee’s techniques, explicit reverberation, is not often seen in flute literature. The flutist is instructed to (optionally) play the marked notes into a piano with the lid up and the damper pedal depressed, creating a lingering ambience. This today might be replicated with a reverb pedal and/or effect.

The opening of the third movement, Refrain, including where to apply reverberation.

Elizabeth R. Austin: Sonata for Flute (1991)

I. A caged bird • II. “Alma redemptoris mater” • III. A singing bird

Austin’s Sonata is an unusual work. Tightly-constructed, yet with spatial and graphic notation; developing structurally clearly, yet with musical collages and quotations appearing throughout. Because of the breadth of musical content, especially the collages, a particularly tricky aspect of this work are the long phrases across varied articulations, breaths, and sudden dynamic changes.

The first movement (A Caged Bird) opens strongly, with a focus on the falling ‘sigh’ figure contrasted by the large jump of a minor ninth

Though flute music is often rooted in birdsong, this is, oddly, the only work in this collection related to birds. The composer writes:

The political upheavals during the time of the Gulf War (and sadly relevant over a decade later) may well have exerted a subconscious influence on this image of the first movement: A caged bird, beating its wings in desperation, sings all the while. In addition, one also hears a disjunct version of a nostalgic World War I song (“Ich hat’ einen Kameraden”) about a fallen comrade.

The variation treatment of the Gregorian chant “Alma redemptoris mater” in the second movement deals with the cross-pollination of the arpeggiated major triad of the chant theme with freer lines. The third movement is inspired by the Chinese proverb, “Keep a green bough in your heart and a singing bird shall come.”

The third movement, A Singing Bird, is mostly meterless and uses spatial notation, in a similar manner to the B section of the first movement.

This is one of two works to have been previously featured in The Flute Examiner. You’ll also be able to take a look at first and second edition differences!

Gina Genova: For Solo Flute (1993)

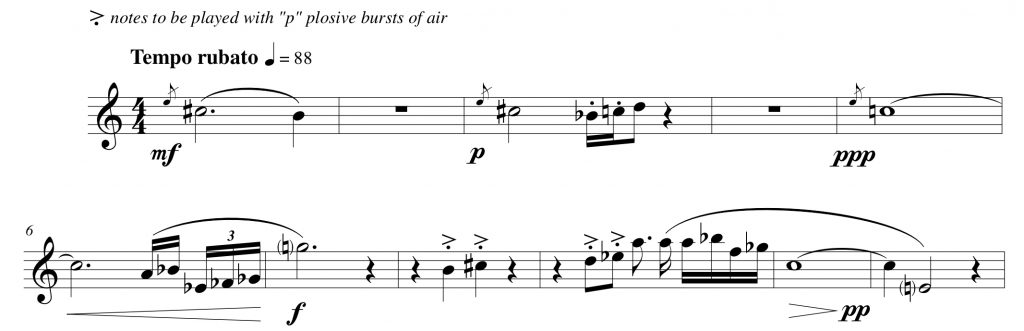

As an archivist, and as a director of various archives across the years, Gina Genova’s musical perspective is particularly wide-ranging. Although For Solo Flute was written while she was still in school—before most of her archival experience—it still betrays a rich musical background; long, luxurious notes anchor the work in tonality, while the connective tissue between explores stranger realms and languages.

The opening six measures drift around the fall from C# to C; the second set of six measures anchor with C and journey to C but, on the way, interject with flourishes and pops.

A particular extended technique, which Genova refers to as “popping” but is today known as a flute pizz, appears throughout the work three times; once in the introduction (above), once right after the central climax, and once during the climb to the penultimate statement. These pops formed the inception of the work. From Genova:

I wrote For Solo Flute after hearing a contemporary ensemble warming up, and seeing their flutist make a sound effect like the sound of popping corn but with a pitch sounding with each pop. It was a fascinating sound and I tried to incorporate the effect in my piece. It was one of the first pieces I composed and it brought great joy in hearing it live.

I asked my grad assistant office mate, the incredible flutist Kathleen Joyce, if she would look over the score for me. I was grateful as she eventually performed the premiere.

Marilyn Bliss: Phantom Breeze (1995)

The solo Phantom Breeze is drawn from Marilyn Bliss’s Wind Songs, a set of two pieces for soprano and Native American flute. Wind Songs was written on a translated Navajo text, and the set thus offers two interpretations. In the first piece, the duet It Was the Wind, Bliss uses the text directly in the soprano part:

It was the wind that gave them life. It is the wind that comes out of our mouths now that gives us life. When it ceases to blow we die. In the skin at the tips of our fingers we see the trail of the wind. It shows us where the wind blew when our ancestors were created.

— Navaho Legends: Collected and Translated.

Houghton, Mifflin and Company. Boston and New York, 1987.

The other piece—the solo Phantom Breeze—offers a second, looser interpretation of the text. Like the other two Bliss works featured in this anthology it begins with a single note around which the flute drifts. Here, though, we find a tonal work, based on the pentatonic tendencies of the Native American flute; where Encounter flexes and turns with microtones and exaggerated intervals, Phantom Breeze more gently sings and gracefully tumbles down scales and arpeggios.

The introductory four measures flick around the middle-register E. The ornamentation, over the next few measures, is extended into a set of falling intervals; first in sixteenths, then in syncopated triplet eighths.

Wind Songs was written for James Pellerite and published under JP Zālo Publications until this year, when American Composers Alliance absorbed the Zālo catalog.

Sarah Meneely-Kyder: Air and Water (1996)

from The Four Elements for Flute and Piano

This pair of flute solos, Air and Water, open Meneely-Kyder’s larger work The Four Elements; the piano does not enter during these extended soliloquies. They are particular rich in coloration opportunity, as the composer relates:

I love the different quality of sound that is produced in the most often used ranges of the flute. The lower range is sultry and velvety, the middle range, stronger and brighter, and the third range, silvery, and piquant.

In Air, the flute opens on a held middle B natural, then swirls and expands around the B in ever-wider intervals (with some connective tissue). A swirling sensation continues through the next phrase as the flute colors the line using a C# – A# tremolo.

Familiarity is most surely another reason for my love of the flute. For many years, I accompanied flutist Peter Standaart, Visiting Artist at Wesleyan University, and Patricia Harper, Adjunct Professor of Flute, at Connecticut College, in numerous recitals throughout Connecticut.

This familiarity with the flute again emerges in the second solo, Water (tears), as the flute shapes the line with idiomatic pitch bends and sighs.

The opening of Water, with heavy use of right-hand open-hole glissando.

The Four Elements was also previously featured in The Flute Examiner.

Margaret Fairlie-Kennedy: Spirit Man (2003)

after the poem by Linda Boyden

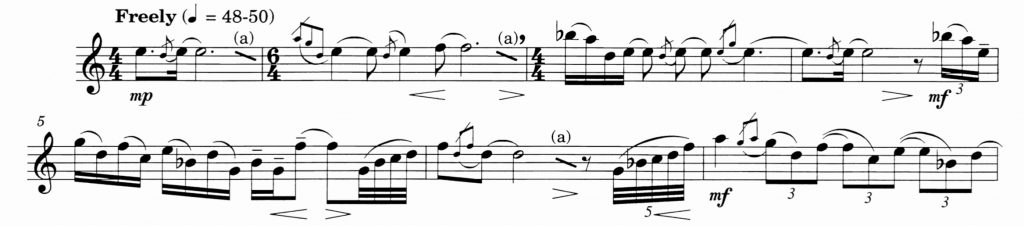

Where Ann Silsbee’s music holds a sense of magical invocation the music of Margaret Fairlie-Kennedy’s plays to open spaces, evocative pulses, and journeys that wind their way up and down extended scale and tonal systems. Here, the three Parts (equivalent to movements) of Spirit Man use a tonal system familiar to those who have played Jolivet’s Chant de Linos – a rich derivative of the octatonic.

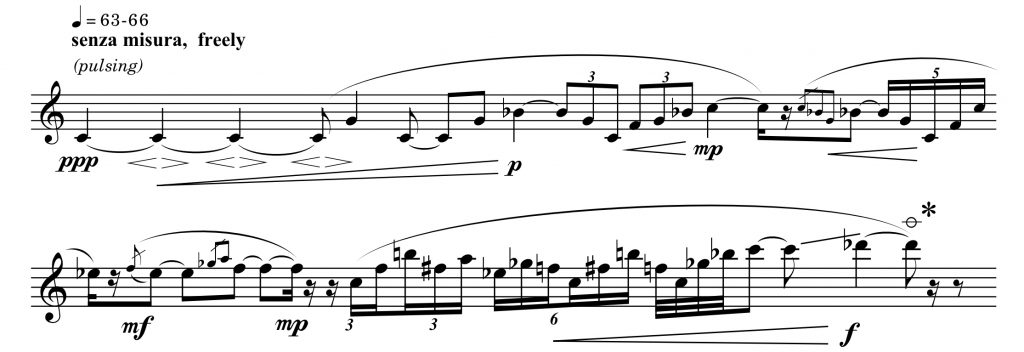

In the opening of Part I, the flute emerges from a slowly pulsing low C, drifting and building. At the end of the phrase it lands on a high C, then shifts up into a D-flat.

Fairlie-Kennedy returns to this A section material, and a rhythmically-driven B section (below), throughout all three parts, though they grow wilder and stranger with each return.

The first appearance of the B section in Part I. Low double-tonguing provides steady pulses against which syncopations help the scale develop.

Spirit Man experienced its first surge of popularity after its appearance in Nina Assimakopoulos’s 2015 album VĀYU: Multicultural Flute Solos from the 21st Century.

Marilyn Bliss: Murali (2004)

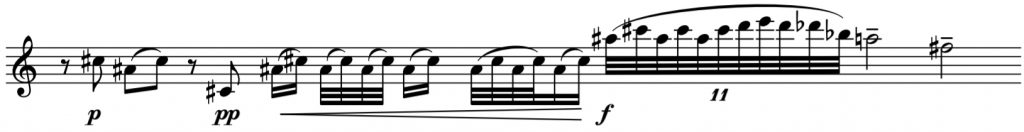

This third Bliss solo for flute is the best-known and most-recorded work in the anthology, though it is still less-known than it deserves. Murali was commissioned by Nina Assimakopoulos, and appeared in her 2014 Points of Entry: The Laurels Project Volume 1 album of music by American women composers; it was after this recording that it began appearing in U.S. competitions. Like Debussy’s Syrinx it is a tale of ancient deities, an ancient flute, and love and lust and supernatural denial. From Bliss:

Murali is the name of Krishna’s flute. In Hindu cosmology and tales, such as those set forth in Robert Calasso’s book Ka, Krishna plays his flute at the first full moon of autumn. It is a very alluring, seductive melody, and it calls to the female cowherds (the gopis), who are all in love with Krishna.

At the sound of Krishna’s flute, the gopis come out of their dwellings and dance, surrounding Krishna. The dancing becomes more and more fevered, when suddenly Krishna disappears from before their eyes.

Soon they once more hear the murali, from a location just beyond the horizon. Is he calling them, or taunting them? The gopis can never decide, but Krishna is always in their hearts.

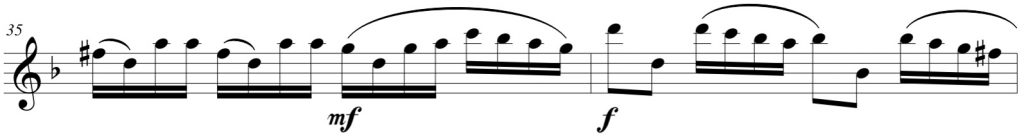

This work, I think, is where Bliss reaches her highest level of refinement in her decorations around a single note, and her development of themes throughout the work. The technical aspects are also (mostly) quite idiomatic.

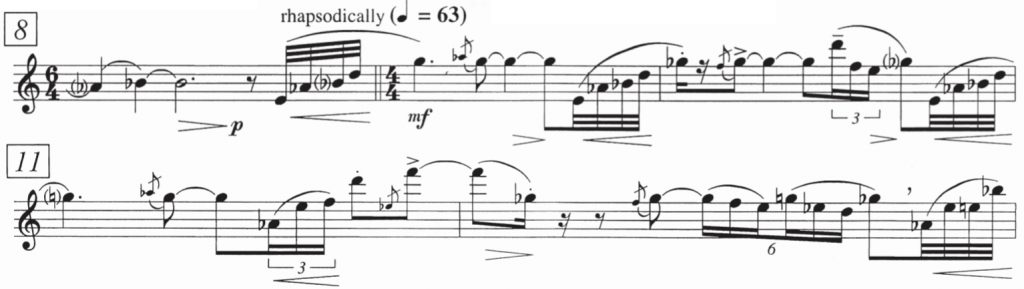

The opening of Murali rotates around G and a fall to G-flat.

Bliss first develops her main theme in the slow, shimmering rhapsody, adding rhythmic and octave displacements and a repeating, insistent arpeggio.

Murali is now featured in The Flute Examiner as this month’s NYWC collaboration.

Joyce Hope-Suskind: Celebration (2015)

Our journey through the solo flute music of these women of New York comes to an end with Joyce Hope-Suskind’s Celebration. It is an intermediate-level work, short yet tightly-packed with Baroque-era development. A remarkable amount of development for such a short work, in fact. The first half is fairly moderate in tempo, but halfway through it accelerates and builds to a short cadenza with more than hints of Mozart.

Celebration opens with a stately theme, not too fast, with lots of opportunity to dig into the tone.

From Hope-Suskind:

Celebration was inspired by the first Women’s March which took place in New York City in August of 1970. The feminist movement had been re-awakened after lying dormant for almost fifty years.

I chose the baroque style because it lends itself to emotional expression on several levels. It combines dignity with vitality and power. The minor key gives a hint of pain but without sentimentality. Rapid runs portray the excitement and joy of this rebirth of feminism.

Smooth harmonic development in the lead-up to the cadenza, matched with idiomatic technical shapes for the flute.

More Anthologies from ACA

Flute Music of New York is the latest solo flute anthology from American Composers Alliance, which began creating collections from archival and new material in 2020 with Flute Works by American Composers. Last year, in 2021, ACA created two flute collections; the anthology Kokû: Twelve Contemporary Solos, with a focus on extended flute and compositional techniques, and Lee Gannon: Music for Flute, which contains all flute works and etudes from the AIDS-casualty composer.